For centuries, theologians have debated the doctrine of total depravity, the belief that people are wholly and naturally corrupt due to original sin. In this episode, Peter Orr speaks with Jonny Gibson, who has edited a 1,000-page book on this topic. They talk about why it’s important for Christians to have a clear grasp of sin, and what can go wrong if we don’t.

Links referred to:

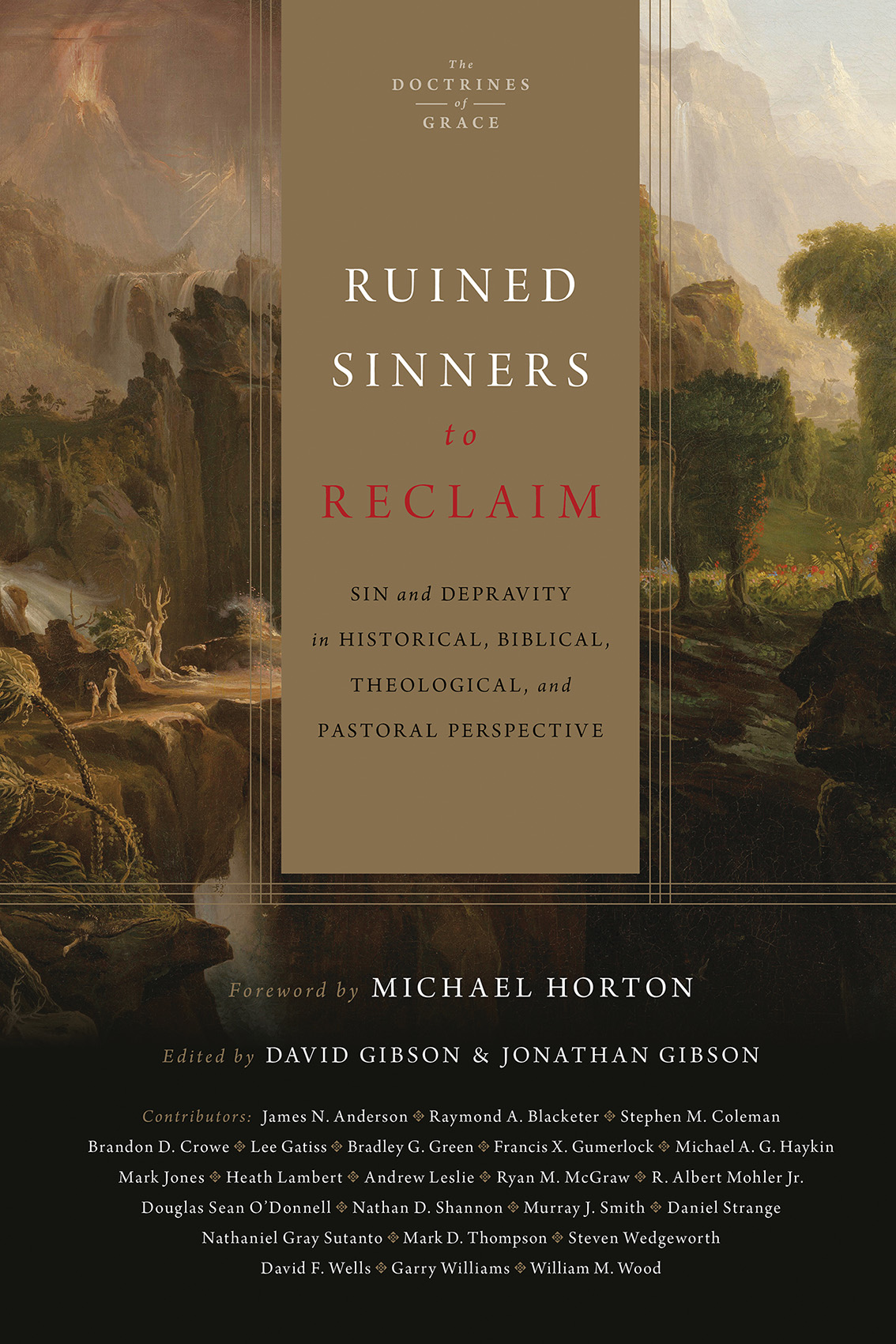

- Ruined Sinners to Reclaim: Sin and depravity in historical, biblical, theological, and pastoral perspective (edited by David Gibson and Jonathan Gibson)

- Episode 123: Losing a child with Jackie Gibson

- Episode 124: The Lord of Psalm 23 with David Gibson

- Our podcast listener survey

- Support the work of the Centre

Runtime: 38:51 min.

Transcript

Please note: This transcript has been edited for readability.

Introduction

Peter Orr: For centuries, theologians have debated the doctrine of total depravity, the belief that people are wholly and naturally corrupt due to original sin. In this episode, I speak with Jonny Gibson, who has edited a 1,000-page book on this topic. We speak about why it’s important as Christians that we have a clear grasp of sin, and what can go wrong if we don’t.

[Music]

PO: Welcome to Moore College’s Centre for Christian Living podcast. Today we’re joined by Jonny Gibson, Professor of Old Testament at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. Jonny, welcome to the podcast.

Now, we’ve had your wife Jackie and your brother David on this podcast. But we appreciate you for who you are, so could you tell us a little bit about yourself—how you became a Christian and how you came into ministry?

Jonny Gibson: Saving the best for last, Pete! [Laughter] Yeah, I was brought up in a Christian home in East Africa. My parents were missionaries there. I heard the gospel from them from a young age. But I think it was when we relocated to Northern Ireland and were attending a good Christian church that I heard the gospel from the minister, but also Mrs Gallagher, who taught me the gospel in Sunday School, and then obviously my parents taught me at home. I think it was then that God opened my eyes to see my sin, my need of a saviour, and how Christ had died and risen again for me.

That was my conversion. I don’t have a moment (although I do have many moments from those days, but I don’t pin my hopes on any one moment), but it was in those days that I think I was born again. We were in a good Christian church for many years, and were discipled well through that. That was really the early stages of my Christian upbringing.

PO: And then the journey into Christian ministry?

JG: I did a gap year in South Africa, which had a big impact on me. I met a Reformed Baptist pastor who introduced me to the doctrines of grace and put me onto good books. Charles De Kiewit: we’ve remained close friends over the years. It’s been about a 30-year friendship!

I then returned to Northern Ireland to study physiotherapy for four years. But during that time, I was brought up in the Christian Brethren, so I was doing quite a bit of itinerant preaching. By the end of my four-year course, I was doing more preaching and Bible study-leading than physio [Laughter] or maintaining my interest in physio. But I didn’t have the money to go to a seminary or a college at the time, so I worked for three and a half years and saved up.

Then in God’s providence, I had a choice to go to Westminster in Philadelphia, and I got a scholarship for Philadelphia. But the timing didn’t quite work out, so I chose Moore College in Sydney, and Jackie is very thankful I did! [Laughter]

PO: That’s right. Jackie your wife is from Sydney.

Ruined Sinners to Reclaim

PG: You have released a number of books, but you’ve just released a book that you’ve edited with your brother David entitled Ruined Sinners to Reclaim: Sin and depravity in historical, biblical, theological, and pastoral perspective. Could you tell us a little bit about the origin of the book and the series that it’s part of?

JG: Yeah, it’s the second book in a series of five. Lord-willing, we are hoping to edit and publish five books on the doctrines of grace. The first book that we did was called From Heaven He Came and Sought Her on definite atonement in those four perspectives—historical, biblical, theological, pastoral.

When we first did that book—and funny enough, that book had its origins in Moore College in Doctrine 3. Mark Thompson or one of the doctrine professors set an essay on limited atonement. I wrote the essay, but in the course of writing the essay, thought it would be really good if there was a book that brought all this together into one volume, because I was having to go and find the historical stuff in one volume and the biblical stuff in another and the theological in another. I said to my brother around the time of my wedding in 2007, “I think there’s something potential for a book on it.” He said, “Let’s put together a proposal.” So anyway, we did, and that was accepted. That came out in 2013 and it was really well-received.

At the time, we just viewed it as a stand-alone volume. But because it was so well received, we had the crazy idea to do four more, and Crossway were crazy enough to be willing to publish the four more, so we got all that signed up in 2016.

This book on sin and depravity is the next in the series. We’re hoping the others will come out soon after, but in reality, the last one on perseverance of the saints will be published by our children, because they’re taking so long [Laughter] The first one took six years, this one’s taken seven, so if you do the maths, I think I’ll be in glory in the intermediate state while my sons Ben and Zachary try to pull the other one together. [Laughter]

Understanding sin

PO: So the topic of this one broadly is sin. We’ll get to the details about that in a moment. But why do you think it’s important for Christians to have a clear understanding of sin?

JG: I think it’s like any illness: if you don’t diagnose it properly, you’re not going to apply the right medicine or undergo the right kind of surgery, and the illness will get worse and you’ll eventually die. So diagnosing is important for prognosis, and for prevention and for medicine.

That’s really like sin: if we’re not clear on sin, then we’re not going to be clear on what the gospel is. You think of what Paul says to Timothy: “The saying is trustworthy and deserving of full acceptance, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners” (1 Tim 1:15). The gospel is predicated on the doctrine of sin, and if we don’t get the doctrine of sin right, we’re not going to get the gospel right.

So if you think that our main problem is sickness, mental anxiety or some sort of relational disorder, and that that’s really what hinders you being a mature, healthy human being on Planet Earth, then you’re going to look for your salvation in a psychologist or in some other system that might actually fix some of those problems. But if you actually understand that your most fundamental problem is that you’re a rebel in the Creator’s world—a sinner—then you realise that you don’t need a psychologist; you need a saviour. I think that’s why I think it’s important we’re clear on the doctrine of sin.

The doctrine of total depravity

PO: More specifically, the book hones in on the doctrine of total depravity. What is the doctrine of total depravity? What does it teach? Why do you think it’s important in particular?

JG: It’s related to sin, obviously, with the word “depravity”. But the adjective “total” really relates to the extent of sin: to what extent does sin affect us? To what extent are we tarnished by sin? Total depravity teaches not that you are as sinful as you possibly could be (that’s a caricature or a misunderstanding of total depravity), but rather than every facet of your being is affected by sin—your thoughts, your desires, you words, your affections, your emotions, your body. Every aspect of your body and soul is tainted and corrupted by sin. That’s really what the doctrine teaches.

An illustration I use is imagine a glass of clean, cold water, and you take a bit of purple dye and you drop it into the water and stir the water. Eventually you’re going to have a glass entirely full of purple water. That’s really what sin does: it’s a poisonous dye that’s put into our being and our nature, and it poisons all aspects of our being.

I think total depravity relates to the doctrine of sin. We’re liable to God’s wrath. We are incapable of any good. We are inclined toward evil in every way, and we are left dead in sin and in slave to sin.

That’s not what every Christian has professed through church history. (I think we’ll come to that later.) But that’s really what the Reformed doctrine of total depravity is trying to speak to.

The concept of total depravity in Scripture

PO: When we turn to the Scriptures, the term “total depravity” is not in the Bible. Should that give us pause? If the doctrine is not mentioned in Scripture, is it really there?

JG: I think this is the whole thing about what Christian theology is. It’s not just a sum of biblical texts—an aggregate of them all added together and put into a paragraph. It’s really trying to synthesise what all those biblical texts are saying, and then synthesise all the internally related doctrines that impinge upon the particular doctrine you’re looking at, and also to assess church history to see how people in the past formulated this particular doctrine.

The doctrine of the Trinity: the word “trinity” is not in the Bible, but we all believe in the doctrine of the Trinity. How do you get there? Well, you hold together various biblical texts, and then you synthesise other biblical doctrines, and you do that in conversation with those who’ve gone before us, the creeds and councils, etcetera.

So total depravity is a theological construct. But it’s rooted in the Bible in the first place, not in speculation or historical theology. It’s in the Bible. Three texts come to mind. There are numerous texts that relate to the doctrine, but I would say Genesis 6:5: “The Lord saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every intention of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.” Geerhardus Vos speaks about four aspects in that verse: he talks about the totality of sin (“every intention”); the intensity of sin (the intent of the thoughts of the heart—the internal aspect); the extensity of the sin (it was only evil); and the constancy of the sin (it was continual). I think that verse really does capture total depravity in one verse: “every intention of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually”.

Jeremiah 17:9:

The heart is deceitful above all things,

and desperately sick;

who can understand it?

That’s how complex the human heart is, corrupted by sin. Then Romans 1:18 “For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men” and Romans 3:11, where Paul gives the vice list:

“None is righteous, no, not one;

no one understands;

no one seeks for God.”

We are enslaved to our sin. We’re not just sick with sin; we’re dead in our sins. More than that, we’re enslaved to sin. I think those three or four biblical texts really root the doctrine in the Bible.

PO: That idea of slavery to sin: Jesus talks about that: “everyone who practices sin is a slave to sin” (John 8:34), and there’s a chapter in your book on that. The other verse I was thinking about is just as an aside when Jesus is talking to his disciples, not his opponents: “If you then, who are evil know how to give good gifts to your children” (Matt 7:11).1 Jesus’ verdict on his disciples is very striking: he thinks they’re evil. It’s confronting. But as you say, it runs throughout the entire Scriptures.

JG: Yeah, you see that sort of enslavement in Romans 6-7—sin having dominion over the unbeliever. In Romans 8, Paul speaks about how without faith, it’s impossible to please God, because we’re enslaved to sin (Rom 8:1-11). Sin is an enemy, and it’s enmity against God, but it also enslaves the Christian.

I’m always struck by the header at the top of Psalm 51: “To the choirmaster. A Psalm of David, when Nathan the prophet went to him, after he had gone in to Bathsheba.” It’s really a huge theological statement: had the prophet not been sent to David, he would never have seen the sinfulness of his sin with Bathsheba. It took a supernatural revelation from God through a prophet to confront him, because he was so self-deceived with his sin (2 Sam 12:1-4). Even when Nathan gives David the parable of the man of the man stealing the other man’s ewes, he’s like, “Bring that man to me and I’ll have him killed.” (2 Sam 12:5) He still doesn’t even see the irony that it’s him. Then the famous words: “You are the man!” (2 Sam 12:1-7). But it’s when the prophet Nathan went to him. That is what is needed because we’re so enslaved to sin.

Historical perspectives on total depravity

PO: As well as chapters on the biblical basis of total depravity, you spend a lot of time considering historical perspectives. Why do you do that? Why do you think that’s important?

JG: I teach my students a thing here at Westminster during the introductory lecture I give called “Beginning with the end in mind”. I try to help them understand why they’re taking this particular course with me, or why they’re at Westminster. I put the curriculum up on a PowerPoint slide and I show them the connection between exegesis and hermeneutics (which are in one box), done in a biblical theological manner (which is in another box) that leads to systematic conclusions (which is in another box). From systematic theology, which faces the world, we’re able to answer the ethical questions and the apologetics questions: who is God? What is man? Who is Christ? Then from there, when we’ve got our systematic theology, ethics and apologetics in place, we can now do pastoral theology. We can preach, we can pastor and counsel, and we can praise God in light of what we’ve seen.

But then I say to them, “Well, where does church history fit in?”, because all of those boxes sort of go along one after the other. I put it floating above and below them, and I do these feedback loops between each of those disciplines within a seminary curriculum, and I say, “What church history does is three things: it is ‘the history of the exegesis of the word of God’,” as Karl Barth said (although he meant something different by “word of God” to what we would mean, but I like his saying: it’s “the history of the exegesis of the word of God”). “It’s the history of the doctrinal formulation—how doctrines were formed—in the midst of fights and heresies. And third, it’s ecclesial preservation: it’s the history of how God preserved his people.” So I say, “Church history does three things: history of how to interpret your Bible, history of how to formulate doctrine, and history of how the church has been kept through the ages.”

That first one’s really important: church history actually gives us the guard rails for our exegesis. It informs us that we weren’t the first people to try to interpret this text, and so we don’t do our exegesis de novo (“from new”) or tabula rasa (“blank slate”). We pick up a chalkboard to do our exegesis, and other people have been writing on it before us, and we should take notice of what they’ve said.

That’s why church history is important, and so that’s why we have this particular section. In each of these books, there will be a section on the perspective of church history, because we want to be informed in our exegesis of how others have interpreted the Bible. But also, because we are looking at this topic downstream (which is obvious; we’re in the 21st century, and the early church has been going since the days of the apostles), we’ve got 2000 years of church history and we want to know the categories—and concepts—that have influenced the discussion on a particular doctrine—in this case, the discussion on total depravity. Church history on the doctrine of sin is really quite fascinating.

1. Pelagianism

PO: You hinted earlier that not everyone throughout history has had the same understanding of total depravity. Could you say a little bit more about that?

JG: Yeah. I think there are four main “isms” that might capture the doctrine of sin in church history. The first is Pelagianism, from Pelagius, the British monk, who was originally from Ireland, but as you and I both know, he’s from south of the border. He wasn’t from the north, let’s put it like that! [Laughter] Hence why he’s a heretic.

Pelagius taught—

PO: [Laughter] For any of our Irish listeners— [Laughter]

JG: That’s right!

PO: Are you a hundred per cent sure he wasn’t Welsh? I thought he was Welsh.

JG: Oh, was he? Oh right. I thought there was a connection.

PO: I think he’s Welsh.

JG: So many “Celtic” is the thing. I thought he maybe spent some time in Ireland. Okay, there you go. Oh, my joke! [Laughter] My joke on the southerners didn’t work! [Laughter]

PO: Your one joke!

JG: [Laughter] Yeah, okay. So he was Welsh. We’ll scrap that.

So Pelagius (4th/5th-century British monk) taught that human beings are born inherently good, and what makes them bad is society, or relationships with other people, or external factors. You’re not born bad. Your will is not corrupt; your will is free. That’s what he taught.

2. Augustinism

Augustine was his big opponent: Augustine confronted this teaching in the church and taught that we were born in sin—conceived in sin—enslaved to sin and dead in sin, and we’d inherited that from Adam. Hence he really was the one who, along the others, articulated the doctrine of original sin—meaning that we had the guilt and sin of Adam imputed to us, because that’s how we’re connected to Adam. We’re connected realistically: we descend from him genealogically and physically. But really, we’re related to him federally, and when he sinned and became guilty before God, we in him also became guilty and sinful.

That was Augustine’s response, which is the second “ism”. Pelagianism: inherently good. Augustinism: inherently evil—not as evil as you possibly could be, but all aspects of your being, especially your will, are corrupt and enslaved to sin.

3. Semi-Pelagianism

Then there was a guy called John Cassian (4th/5th century). He rejected Pelagianism, but he didn’t quite want to go with everything Augustine said. He didn’t quite like his doctrine of predestination; he wanted it to be a bit more conditional. With regards to man, man was not inherently good, but he wasn’t inherently bad either; it was sort of a mid-way. He was weakened by sin, not enslaved by sin. He still had something of a free will.

He taught that man would make an initial move towards God, and God would come and meet him in his grace and complete that move, and he would be saved. This was what became known as “semi-Pelagianism”, the third “ism”. The patient was sick and needed a helping hand. The patient wasn’t dead and needed resurrecting, like Augustine would say; the patient was sick. It really presented a synergistic salvation. Pelagianism presented a sort of auto-soterianism, where you save yourself, because you were inherently good and you just needed to improve yourself. Semi-Pelagianism was saying, “No. You do have a problem, but you work with God.” There’s a synergism there to your salvation.

Roman Catholicism is really semi-Pelagianism: the human being is born tainted by sin, but the grace of the church can be infused into that person, and they can then be saved. But also, the person can resist the grace of God. That’s the other thing that John Cassian would teach—that the human person still had enough of a free will to resist God’s grace.

4. Arminianism

Well, the fourth “ism” is Arminianism, which is not, strictly speaking, the same as semi-Pelagianism, but has a number of affinities with it. What Arminius in the 16th century and his followers, the Remonstrants, in the 17th century did is he flipped the order: God’s grace comes to you first; it’s prevenient grace; but as a human being (very like Semi-Pelagianism), you are tainted by sin, but you’re more weak than dead. You have a free will, and you can resist God’s grace, if you so choose. But if you, by your free will, choose not to, then you’ll be saved. It’s very similar to semi-Pelagianism, but as I say, technically, the order of grace and free will flip around in Arminianism.

Pelagianism, Augustinism, Semi-Pelagianism and Arminianism in modern life

In one sense, you could condense those four down into three. Pelagianism: man is morally well. Semi-Pelagianism and Arminianism: man is morally sick and weak. Augustinianism: man is morally dead and enslaved. That’s where church history is so helpful: you can now work with these three categories.

In modern life, if you look at our secular and secular psychology or psychiatry, you’ll see it’s inherently Pelagian. We are inherently good or neutral. Yes, we’re not perfect. But the sin or the bad that we have in our human nature—the immaturity, the problems in our relationships, whatever they are—they have come to us from outside us. The problem is not in us; it’s outside us. It’s society. It’s our relational family tugs and ties. These are the things that affect our humanity and pull us down from being as good as we could be. They’re inherently Pelagian: that’s why they preach a false gospel.

The answer is not Semi-Pelagianism in Roman Catholicism. It’s not Arminianism, which is in a lot of evangelical churches. The answer is a good, solid Reformed doctrine of Augustinianism with respect to sin, and therefore, a Monergistic view of salvation—that only God is at work, ultimately raising the dead, releasing the slave and giving them new life, and putting the desire in their heart to seek after God, because, as Paul says in Romans 3:11, “no one seeks for God”. Until God comes looking for us, we’re not going to go looking for him. I think Adam in the garden is a good example of that: he’s hiding and it’s God who comes looking for him; he doesn’t go looking for God (Gen 3:8-10).

[Music]

Advertisement: Podcast survey

Karen Beilharz: Podcast producer Karen Beilharz here. For the first time ever, we are conducting a listener survey to help us get to know you and how you interact with the CCL podcast.

We’d love it if you could fill it in. There are only 10 questions, and they’re on stuff like how long you’ve been listening to the podcast; whether you listen on your phone, your tablet or your computer, or if you just read the transcripts; and what you most like and least like about the podcast.

It should take around 5-10 minutes to complete, and your responses will really help us as we consider how to improve the podcast, moving forward.

You can find the survey link in the episode description or the show notes, or visit ccl.moore.edu.au/podcastsurvey/.

Thank you again for your support!

PO: Now let’s get back to our program.

Theological implications

PO: You’ve touched on some already, but what are some of the theological implications of the doctrine of total depravity?

JG: I think the main one is we cannot save ourselves and that God has to come to us in order for us to be saved. We know that he has done that in the person of his Son. Because of the Creator/creature distinction, in order for God to actually mediate or provide a mediation for us or an atonement, he has to actually become one of us, and we know that he’s done that in the person of his Son.

But his Son cannot descend from the human race. He cannot be begotten of Adam, otherwise he inherits the sinful nature and he is a member of the covenant of works, and Adam is the head of the covenant of works, and so Adam would input to him guilt and sin. That’s why the virgin birth is so crucial to our doctrine of Christ—that he was not begotten of Joseph. He was conceived by the Holy Spirit in the womb of the Virgin Mary, so he could have a perfect human nature and then live a perfect life under the law, credit righteousness to us because of that, and then die the death that he didn’t deserve, but that we deserve for our sin to give us the forgiveness that we need.

And then he was raised to new life and entered into a state of humanity that is incorruptible. That’s the glorified state: Christ in his resurrection state is in his glorified state, which is the state of humanity to which he will escalate us.

So in Reformed teaching, they talk about the four states of man. I think it was Thomas Boston who wrote the book, Human Nature in its Fourfold State: man is made in the state of innocence—original righteousness. He falls into the state of sin. God rescues him into the state of grace. But that’s not the end: God is waiting to escalate us into the state of glory. That escalation is only possible because of what Christ has achieved in his life.

I was reading Geerhardus Vos this week. He said Christ does not win for us what Adam lost; Christ wins for us what Adam could have achieved for us. Adam never escalated humanity into the state of glory. He was in a state of innocence and righteousness, but it wasn’t confirmed righteousness. It wasn’t the immutable, glorified state, body and soul. It was an unstable state: Adam could sin; Adam could not sin; it was his choice. Christ takes us into a state of confirmed righteousness—of immutable glory—where we cannot sin. He escalates us.

So you can see that the doctrine of sin and depravity is connected to these kinds of theological discussions.

PO: And as you point out, you talked about the glory of the gospel. So having a clear view of our sin and our depravity, yes, it should sober us. But also, it points us to the wondrous glory of Christ and what he has done for us. So it’s a tremendously encouraging doctrine in a strange way, because it shows us the beauty of Christ.

JG: Yeah. Nancy Guthrie, who kindly endorsed the book, said that as she was reading it, she found herself quite burdened by the chapter after chapter on sin. And yet, she said she found herself really delighting and rejoicing in the gospel at the same time—that “Wow, what God has saved us from in Christ is just amazing!”

Pastoral implications

PO: As well as the historical perspective and the theological implications, there are also a number of chapters drawing out the pastoral implications of the doctrine. Could you say something about some of the pastoral implications of this doctrine?

JG: I guess it goes back to that point—that if you don’t get the diagnosis right of an illness, then you’re not going to apply the right medicine or take the right radical surgery that’s needed to deal with the problem. I suppose that would be, perhaps, in the area of concupiscence, which is really the technical word for desire or passion or lust. The New Testament speaks about good desires and good passions, but also the majority of uses of the word or word group is negative. It’s sinful. It’s lust. It’s lust of the flesh.

What do you do with concupiscence? Is concupiscence sin? Some people like to say, “No, it’s not good that you desire those things. But as long as you don’t act on them, you haven’t sinned. The desire is only sin if it’s acted upon.” Often James 1:13-15 is quoted:

Let no one say when he is tempted, “I am being tempted by God,” for God cannot be tempted with evil, and he himself tempts no one. But each person is tempted when he is lured and enticed by his own desire. Then desire when it has conceived gives birth to sin, and sin when it is fully grown brings forth death.

People are tempted. God doesn’t tempt anyone, but people are tempted by their own desires—their own concupiscence, their own sinful desires—they are led into temptation, and if they give way to the temptation, then they sin. People think, “Okay, there you go: there’s a distinction between temptation and sin, so temptation itself isn’t wrong. If you feel some lust in your heart for something—whatever it might be—money, car, another woman, another man—as long as you don’t act on it, you haven’t sinned. But that’s really a Roman Catholic doctrine of sin, and that’s one of the things that this book tries to really make clear: we have a whole chapter on concupiscence. Stephen Wedgeworth writes that one, and he traces the doctrine all through church history. Then he applies it into contemporary contexts with some contemporary writers, and engages where he thinks they’ve gone off either side of the road with regards to concupiscence.

The practical issue today—or at least a common one—is the discussion of same-sex attraction: is same-sex attraction sin? I think evangelicals have inadvertently (not deliberately) slipped into sort of a Roman Catholic view same-sex attraction: “As long as you don’t act on it, you’re not sinning.” But Protestant Reformed orthodoxy taught that any concupiscence that is sinful—desires, lust—is itself sin. Even if you don’t act on it, just the fact that you have the desire is itself sin and is to be repented of. The Thirty-Nine Articles speaks about sin—concupiscence—being “an infection of nature” (Article 9). The Apostle does confess that concupiscence and lust has, of itself, the nature of sin (Col 3:5; Rom 7:7-25), and if it has the nature of sin, then it is to be repented of.

This is the distinction between original sin or what other Reformers would call “habitual sin” (Peter Vermigli calls it habitual sin), and actual sin—the act of sinning. What’s interesting in the liturgies of the Reformers is that they, in their confessions of sin, speak about confessing not simply the acts of sin, but also original sin—habitual sin. Both are confessed before God, and the request is made for forgiveness and that the Holy Spirit would renew our natures—renew our thoughts—and lead us to walk in ways that are worthy of him.

I think this is an important area from a pastoral perspective, because if we don’t get this right, we’re going to leave people in their sin and we’re going to let them create little fiefdoms. It might not be same-sex attraction; it might be some other lust or sin or covetousness. Whatever it is, they will think, “So as long as I don’t act on it, I’m not actually sinning”, and it becomes a little fiefdom in their lives that the Holy Spirit and the minister, as he preaches the word, is not allowed to go into. He’s not allowed to touch it, because that’s the little domain of my identity, or that’s just who I am. It’s come down to me; I didn’t choose it. I think this is where, hopefully, our book can start to speak into some of those issues and actually show that we really need to get the doctrine clear and the theology clear, so that we can get the pastoral application clear.

The victorious Christian life

PO: What about this idea that as Christians, we should be living the victorious Christian life? How does the book speak to that idea?

JG: I think you’ll find that, in the end, we have a chapter in the book by Mark Jones on “The sinlessness of Christ”. That was a deliberate move on our part, because it’s a book full of sin and we thought, “Well, let’s actually have something positive to say!” [Laughter] I wanted a chapter where we could not just hold Jesus up as an example of a sinless person, but to show that our salvation is dependent on him being sinless.

Now, Christ died for our sin as the sinless one, so there’s the “for”/“on behalf of”/“in the place of”/“as a substitute” idea. But Romans 6:10 says he died to sin: that preposition “to” is really important. He didn’t just die for the penalty of sin; he died to the power of sin. Paul in Romans 6 makes the point that precisely because Christ died to the power of sin—to the dominion of sin—sin did not have any dominion over him ever in his life. Because he died to it, we should not let sin reign in our bodies (Rom 6:12). It should not have power over us.

Therefore, the victorious Christian life is something that we should be talking about and living—so long as we also qualify that with, “You will never be entirely victorious until you’re glorified or enter the intermediate state.” But you are in Christ. Sin no longer have dominion over you.

I think this is the problem with the same-sex attraction discussion: when people put that compound adjective on the front of “Christian”, it’s an oxymoron. “I’m a same-sex attracted Christian.” That would be like me going around saying, “I’m an other woman-attracted Christian” or “I’m a covetousness-attracted Christian”. Do I struggle with covetousness? Sure. If I meet an attractive woman, do I have lust in my heart that rises? Yes, I have to put it to death. But we don’t go around identifying ourselves with a sin on the front of the word “Christian”. We’re Christians. We’re not yet perfect, but we’re Christians. We’re in Christ. Sin shall not have dominion over us. So let’s talk like we’re Christians. We are in Christ. We’re putting to death the deeds of the flesh. But we’re not to identify with that old world—with the present evil age. We are now seated in the heavenly realms (Eph 2:6). We now belong to the age to come. It has broken in in Christ’s resurrection, and Christ is coming back to consummate that age in his return. We belong to that age—to the heavenly age—not to the earthly age. So to find Christians identifying themselves with what belongs to the earthly age is really quite concerning.

It’s also really liberating—that if you are struggling with these things, you can view yourself as in Christ, connected to the age to come, seated in the heavenly realms, and therefore, by his Spirit, you have the power to put those things to death.

Conclusion

PO: Wonderful! Jonny, thank you so much for your time with us today. Thank you for editing this book. It’s a wonderfully rich reflection on this very important doctrine.

I thought I might finish just by reading the verse of the hymn by Philip Bliss that the title Ruined Sinners is taken from. It’s a wonderful hymn that we sadly don’t sing—well, certainly in my circles—we don’t sing very much these days,

Man of sorrows, what a name

For the Son of God who came.

Ruined sinners to reclaim:

Hallelujah, what a saviour!

Amen.

[Music]

PO: To benefit from more resources from the Centre for Christian Living, please visit ccl.moore.edu.au, where you’ll find a host of resources, including past podcast episodes, videos from our live events and articles published through the Centre. We’d love for you to subscribe to our podcast and for you to leave us a review so more people can discover our resources.

On our website, we also have an opportunity for you to make a tax deductible donation to support the ongoing work of the Centre.

We always benefit from receiving questions and feedback from our listeners, so if you’d like to get in touch, you can email us at [email protected].

As always, I would like to thank Moore College for its support of the Centre for Christian Living, and to thank to my assistant, Karen Beilharz, for her work in editing and transcribing the episodes. The music for our podcast was generously provided by James West.

[Music]

Endnote

1 In the recording, Peter says “Mark”.

Scripture quotations are from The ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Photo by Jade Koroliuk on Unsplash