Vaccination. Vaccine Passports. Global Warming. Refugees. Wading into these waters during your lunch break or at a family get-together is a rather perilous task. Throwing a few words out onto the World Wide Web is far easier. I’m feeling rather comfortable sitting here at my dining table in my trackies with a hot coffee, many kilometres away from the nearest person who might read this and disagree with me. But even so, I have no great desire—or courage!—to add my two cents to any of these discussions.

Instead, a larger concern on my mind is the way we as Christians can approach these discussions in our churches, rather than the particular issues themselves. As our society becomes increasingly divided along political lines, the Bible’s emphasis on unity in the church has been standing out to me more and more. It’s striking that almost every New Testament letter includes either a call for harmony or a warning against divisiveness: we are called to “live in harmony with one another” (Rom 12:16) and to “[eagerly] maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Eph 4:3). Unity in the workplace and in extended families is a wonderful thing, but unity in the church is essential.

To be sure, Christian unity is certainly not an absolute principle; there are certain issues the church should divide over. For example, we can’t agree to disagree about whether Jesus really rose from the dead in the name of “Christian unity”. Instead, we are commanded to maintain the unity of the Spirit: the essentials of the faith that unite all Spirit-indwelt believers must not be compromised. But when it comes to the hot button political issues of the day, we are called to a radical counter-culture of peace and unity.

So how can we foster such a culture of unity in the church while remaining open to discussing these issues? Here are three principles that come to mind.

1. Assume the issue is more complicated than you think

First, assume the issue at hand is more complicated than you think it is. Disagreements among Christians are much more likely to cause tension or conflict if the issue is misdiagnosed as a simple problem with a simple solution. Consider these questions:

Should Christians get vaccinated against COVID-19?

Should Christians support the elimination of fossil fuels?

Should Christians support an increase in Australia’s refugee intake?

For some, the answer to all of these questions is very simple: we are called as Christians to love others, so the answer is, “Yes, yes, and yes!” At one level, the task of Christian ethics is really that simple: Jesus summarised the entire Old Testament law as a command to love (Matt 22:37-40). James says that if we love our neighbour as ourselves, we are doing right (James 2:8).

Why, then, is there still disagreement among Christians on these questions? If biblical ethics is as simple as “love your neighbour”, why aren’t we all on the same page?

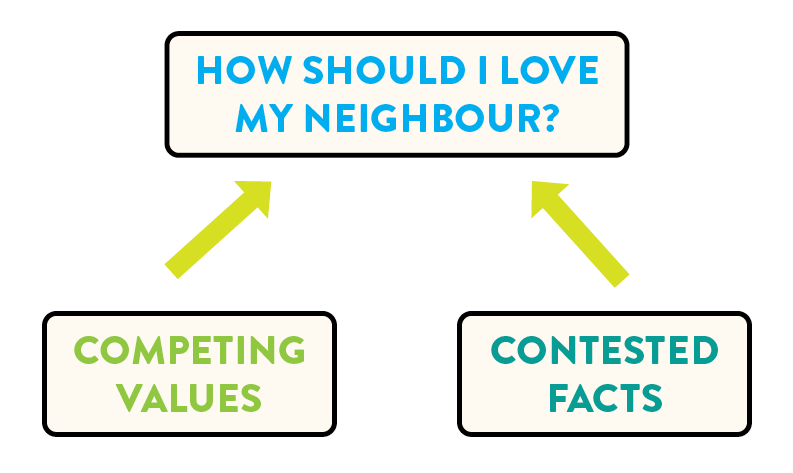

Unfortunately, the task of working out how to best love our neighbour is not always a straightforward one. There are, broadly speaking, two complicating factors at play: competing values and contested facts.

When thinking about climate change, for example, there are competing values that need to be taken into account. We value enjoying and developing God’s creation, but also protecting and preserving God’s creation. We value both present prosperity and sustainability for the future.

At the same time, responding rightly to climate change relies on a knowledge of certain contested facts. What effect do various human practices have on the average global temperature? What effect is this change in temperature having?

Complicating this even further is the need to take future facts into account as well. How efficient and effective will future technologies be? Will future generations be able to adapt to warmer temperatures?

When there is disagreement among Christians about a secondary issue, it is not enough to simply insist that we act in love for our neighbour. The heart of the disagreement is almost always deeper—on the level of either competing values or contested facts, or perhaps both. Realising this can take the heat out of our discussions as believers. Our brother or sister in Christ may be mistaken in their values or facts (or we may be—see point 2 below), but they are likely coming from the same basic position of looking to love others. If we have connected tightly our position on contested issues to a simple biblical command to love others, we are not likely to be generous to anyone who sees things differently.

2. Listen with humility and genuine curiosity

Second, we can maintain unity in our churches by practising and promoting humble listening and genuine curiosity in our conversations. Whether the issue at hand relates to values or facts, a crucial weapon in the church’s fight to maintain unity is an attitude of humility. The practice of humble listening lies at the heart of biblical wisdom when it comes to personal relationships:

A fool takes no pleasure in understanding,

but only in expressing his opinion

(Prov 18:2)

If one gives an answer before he hears,

it is his folly and shame

(Prov 18:13)

Know this, my beloved brothers: let every person be quick to hear, slow to speak, slow to anger (James 1:19)

When it comes to issues we are passionate about, it is much easier to speak than to listen. It is much easier to dismiss a different view before we’ve taken the time to hear it reasoned out. My instinct is to think about the issues and facts the other person needs to consider, but in contrast, a posture of humility takes pleasure in understanding. Let’s ask ourselves in our disagreements with others, “What’s something I need to go away and think about some more? Are there any facts I have assumed that I need to investigate further?” This certainly doesn’t mean we will agree with each other; that may still be quite rare! But it means that we will be less likely to attribute motives that aren’t there and more likely to identify the competing values and contested facts that are actually at play.

The same principle can also be applied to our engagement with news media and social media. Are we listening to different viewpoints in the media with an openness to changing our minds? Platforms like Facebook and YouTube, by their very design and usually by our own preferences, promote confirmation bias: we’re likely to see and engage with content that confirms our opinions, rather than challenging them. We will do well instead to engage in humble listening to differing perspectives—both online and face-to-face.

3. Major on the majors

Thirdly, we need to major on the majors—that is, keep our focus and emphasis on the glorious truths of the gospel and the response it calls for in each of our lives. It’s not only the way we speak about these controversial issues that is important, but also how much we talk about them. If you’re anything like me, it’s easy to get swept up with the latest news and political developments. We are often drawn to the new and the now, scrolling through news sites or social media to make sure we don’t miss something. So it’s easy for our conversations at church and other Christian gatherings to focus on these current events and neglect the things that unite us as believers.

This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t discuss social and political issues. It’s just that we need be wary of where we’re placing our emphasis. We need to avoid an “all or nothing” approach: something can be important without being the most important. If Paul can speak of things “of first importance” (1 Cor 15:3) and “disputable matters” (Rom 14:1 NIV), we can reflect this approach as well. We can major on the majors without discarding the minors.

To do this, however, we need to ask ourselves some tough questions from time to time. Are our conversations at church more often about current events than about the sermon we’ve just heard? Are we developing more evangelistic zeal for a certain political opinion than for the gospel? When it comes to our daily habits, are we taking in more from our news feed than from God’s word? Do we spend more time criticising the government than praying for the government?

Maintaining Christian unity in a divided culture is, no doubt, a significant challenge we are facing and will face in the months and years to come. But it is also a priceless opportunity: on the night before he died, Jesus prayed for “those who will believe” in him—that is, for us (John 17:20). He prayed that we would be united as one “so that the world may know that you sent me and loved them even as you loved me” (John 17:23). Our unity is one of the means by which God has chosen to reveal himself to the world. As our culture divides, a community that discusses hot button issues with humility and gentleness will stand out more and more. Visitors in our churches will notice.

In the kindness and providence of God, we find ourselves in such a time as this. But instead of being discouraged by the division we see in our world, let’s make the most of the opportunity to be the “light of the world”, shining before others “so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven (Matt 5:14, 16).

Sam Davidson has just completed his third year at Moore College.

If you enjoyed this article, check out others like it in the CCL annual.

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from The ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.