Our culture is obsessed with identity: we’re often told, “You do you” and encouraged to live according to our “true and authentic self”, expressing publicly how we feel about ourselves internally.

However, the very concept of personal identity is inherently slippery. It encompasses things like ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, religion, belief, educational background, profession and personality, but it’s not fixed: it can change through time, circumstance, and even through self-invention.

So as Christians, how should we regard identity? God created us as unique individuals; how does our creatureliness affect who we are? Furthermore, as sinners redeemed and sanctified by the Lord Jesus and adopted into the household of God, how does Christ’s work change the way we view ourselves? How does the encouragement to “find your identity in Christ” actually play out in the complexities of competing sources of identity?

At our final event in our series on “Culture creep” in October 2024, Rory Shiner, Senior Pastor of Providence City Church in Perth, showed us how losing ourselves for the sake of the kingdom will help us find ourselves once and for all (Matt 10:39).

Links referred to:

- Watch: Who am I? The search for identity with Rory Shiner

- Our podcast listener survey

- Support the work of the Centre

Runtime: 51:05 min.

Transcript

Please note: This transcript has been edited for readability.

Introduction

Peter Orr: Our culture is obsessed with identity: we’re often told, “You do you” and encouraged to live according to our “true and authentic self”, expressing publicly how we feel about ourselves internally.

However, the very concept of personal identity is inherently slippery. It encompasses things like ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, religion, belief, educational background, profession and personality, but it’s not fixed: it can change through time, circumstance, and even through self-invention.

So as Christians, how should we regard identity? God created us as unique individuals; how does our creatureliness affect who we are? Furthermore, as sinners redeemed and sanctified by the Lord Jesus and adopted into the household of God, how does Christ’s work change the way we view ourselves? How does the encouragement to “find your identity in Christ” actually play out in the complexities of competing sources of identity?

At our final event in our series on “Culture creep” in October 2024, Rory Shiner, Senior Pastor of Providence City Church in Perth, showed us how losing ourselves for the sake of the kingdom will help us find ourselves once and for all (Matt 10:39).

In this episode, we bring you the audio from that event minus the Q&A segment, which you can find on our website: ccl.moore.edu.au.

We hope you find Rory’s talk helpful as you think about your identity in Christ.

[Music]

PO: Well, good evening and welcome! My name is Peter Orr, and I’d like to welcome you to our fourth Centre for Christian Living event of 2024. The Centre for Christian Living is a Centre of Moore College that exists to bring biblical ethics to everyday issues.

This year, we’ve dedicated our four live events to exploring the idea of culture creep and the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Romans, where he talks about not being conformed to this world. I’ll read that passage in a second.

This year, we’re looking at different temptations we face to be conformed to this world. Previously, we’ve thought about technology—particularly AI; we’ve thought about casual sex; we’ve thought about wealth; and tonight, we’re thinking about identity.

We’re very privileged to be joined by Rory Shiner, who has flown in from Perth to be with us tonight to help us to think about the question of identity. We’ll get to know Rory in a moment.

Let me start by reading that passage I mentioned and then praying. This is what the Apostle Paul says:

Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship. Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will. (Rom 12:1-2)

In response to what I’ve just read and in anticipation of what we’ll hear this evening, why don’t we pray.

Our Father,

We thank you for this time that we can meet together and think about the question of identity. We pray that you would help Rory as he explains your word and helps us to think about how it relates to the world that we live in. Please help us to listen carefully and to respond in a way that honours the Lord Jesus.

We ask it in his name. Amen.

I’ll call Rory up and we’ll get to know him.

[Applause]

An interview with Rory Shiner

PO: Rory, tell us a little bit about yourself and your family, and then how you became a Christian.

RS: My name’s Rory. Great to be with you. I’ve left behind a wife and four kids. We’re all under one roof—four boys. It’s really great to be with you tonight.

I had the privilege, which I hope lots of you have had, of being from a Christian family. I think the double whammy there was that they believed in and taught us about the Lord Jesus Christ, and they lived lives that checked out—as in, whatever else I ended up believing, they definitely believed that Jesus was real and that he had brought them into salvation. That’s my story: through them, and probably like lots of people in the room, I accumulated a few scrapes and bruises along the way, with some untoward behaviour during high school and all that sort of thing, and I entered into a settled, mature, adult faith at 19 at university. Here I am.

PO: Here you are and you’re a pastor of a church in Perth. How did you go from the 19-year-old mature faith to being a pastor?

RS: Yes, so at university, that’s where I got “radicalised”: I got involved with a Christian union there. The significant thing there, which wasn’t as much a part of my background, was just a really credible way of using the Bible and having God’s word at the centre of Christian ministry. That really did something in me.

Then the main staff worker for the Christian union took me aside, and I kind of ended up ministry under false pretences or a misunderstanding. He took me aside and he said, “Look, I think you should come and do ministry training. What we do is raise support for about $26,000 a year.” Two things occurred to me: one was, “Oh my goodness! He must think I’m great. He’s asked me to do this thing”, and, “$26,000 a year? That’s more money than I’ve ever seen before in my life!” [Laughter] So I thought, “This is unbelievable!” Since then, I’ve discovered that $26,000 a year is not amazing, and it turned out the guy was asking everyone [Laughter] to do ministry, and so there was nothing special about me. But on that false pretence—

PO: Here you are!

RS: Here I am! [Laughter] That’s right: it’s just been too awkward, to get off the conveyor belt, having got on to it.

PO: Rory and I were just chatting about ministry and what would be a good question to help you get to know him. So I was going to ask what’s harder now at this stage in ministry than it was at the beginning, and what’s easier at this stage of ministry than it was at the beginning?

RS: The easier one first: say for example, preaching. Preaching is not all of ministry, but it’s a big part of ministry. I think you get to a point in preaching where the shadow of fear recedes to about 10 o’clock the night before. When you start, the shadow goes to about Wednesday of the week before, and you live in dread of having to deliver this preaching. This is a bit of inside baseball, but it’s like an exam that you can’t write and say, “Listen, I’m not quite ready yet,” because church is starting at 11 o’clock today. You just do the thing. That gets to a point where you manage it. I don’t think you ever get to zero anxiety, but you can manage that in a liveable way.

The boring thing that gets harder—well, the generic thing that gets harder is the leadership thing. As things grow and develop, you get to a point where everything that could have been solved would have been solved before it got to you. So everything that gets to you is difficult, ambiguous and unwinnable. I think that’s true of anyone in leadership. I’m sure people here would recognise here.

Maybe a specific one that is relevant tonight is I think our culture is uniquely ill-equipped to deal with chronic, as opposed to acute, problems. One of the things you discover in ministry, which you’re not confronted with at university, is sometimes people just have problems that don’t fix—that go on indefinitely at a kind of heart level. That’s poor thing where there’s ways in which our culture sells us short in our ability to make sense of and care for people in chronic situations.

PO: Thank you, Rory! I’m going to hand over to you.

Part 1: Who am I? The search for identity

RS: Excellent. Well, it’s great to be here, so thank you very much for coming out tonight. I’m really glad to be thinking with you about these things.

Introduction: Identity

Three goals

I’ve got three goals, and therefore you’ve got three ways of marking tonight’s assessment and seeing whether it pleases you or not, or whether I’ve achieved according to the rubric. Here we go.

Firstly, I want to describe as best I can the way we moderns go about answering the question of “Who am I?” I think we do have a very distinct way of doing that, and I want to ask for high marks if the way I describe it is resonant. My aim in that section is that you recognise it, and you say, “Yeah, that sounds like how we do it.” That’s the first section: to faithfully describe how we go about constructing identity and how we go about answering the question “Who am I?”

The second thing I want to do is find fault with that. Having described it fairly impartially, I do want to, at that point, pick at it and criticise it—to point out some of its weaknesses and shortcomings.

But then, in a surprising move that no one saw coming, I want to turn to the idea of finding your identity in Christ, and instead of seeing that as the obvious no-brainer solution, I want to find a little bit of fault there too. I want to raise the idea of “find your identity in Christ”, and at least tease that out or think critically about that as a kind of panacea solution to our pastoral and personal problems, because, to quote The Princess Bride, when we use that kind of language—“find your identity in Christ”—I don’t think that word means what we think it means. [Laughter]

Then finally, having shocked you with that dangerous move, peace will be restored and I’ll say something positive about being in Christ and how that could work in a kind of more complicated, but interesting, way to shape our sense of who we are and how we live.

Ready for this journey? Let’s do it!

1. Constructing the modern self: How to put you together

Our first part is thinking about how we construct the modern self. I take it by your presence here, you think that this is a topic—that something’s going on—that the way we use the language of identity is having a moment. We think about identity politics. We construct in social media online identities. We see a shift in language—a subtle, but interesting one—from saying “I am a zealot” or “I am a Christian” to “I identify as a zealot or Christian”. Something’s going on there that’s interesting.

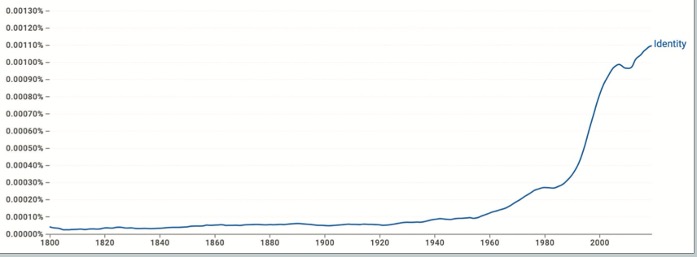

The word identity” is a fairly new word. It’s got a bit of a background, but it really emerges in the way we use it out of sociology and social psychology in the first half of twentieth century. As you can see on this graph from an article by Nathan Campbell in Zadok, it explodes in usage after World War II and especially during the 1960s.1

I’m not doing anything with that graph except to just let you look at it and note that that’s interesting—that the language of identity doesn’t come out of the Bible,2 but for whatever reason, it suddenly becomes useful in our culture very dramatically and very recently.

Perhaps at the pointy end of this issue, you have the transgender debate where, ironically or interestingly, at a science level, one of the things we have discovered is that gender or sex goes deeper than we thought. For example, if I rubbed the lectern, a forensic scientist could come in tomorrow and say not only that there’s a smudge left by a human, but in some weird way, it’s a male smudge that I left behind. But the transgender debate isn’t really a debate about science, but about naming rights—about identity. Does my culture or the science or even my own body have naming rights over me? Who gets to say who I am?

That’s the space we’re occupying tonight and the issues that come up for us in this area of identity. So first of all, I want us to think about how we construct our identities as moderns.

The Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor talked about “sources of the self”.3 That’s his way of thinking about it: what are the sources by which we construct selves as people in modernity?

You (but in 1524)

Rather than bore you with a description of that, I wanted to do a little thought experiment. But you’ve got to come with me for it to work. I want you to think about you—physically, psychologically, biologically and IQ-wise. Everything about you is the same. I’m just going to introduce one variable to you, which is that imagine if you had been born 500 years ago. Let me have a go at this: how would you have constructed yourself if you had been born then?

Well, you would have been born into a context in which you were one of eight/ten/maybe twelve children—several of whom would have died before their fifth birthday. You would have known with 99 per cent accuracy what you were going to do when you grew up, because it was shaped by two unchangeable realities, which were your gender and your family of origin. If you were a boy and your father was a farmer, you were going to be a farmer. If you were female, you were going to be a wife and a mother in that context.

So in that context, you never had the conversation, “So what are you going to do when you grow up?” You never heard a graduation speech about following your dreams [Laughter]. Your parents never said to you, “Look, the main thing about your job is that you enjoy it—that you really get into it.” [Laughter] Most of the wisdom that was available to you—that is, the folk songs that you sang, the advice from your elders, the stories that you knew, the poems that you learned—were about how to cope with given realities. They were about the wisdom of making peace with the hand that had been dealt to you.

Your life was communal: you had next to no privacy. There were always people around. The world that you looked at was—another Charles Taylor word—“enchanted”: there were spirits, demons and forces in the world that were beyond your control, and everything meant something. The question was not whether it meant something, but what it meant. The thunderstorm might mean that God is angry with you. The failure of the crops might mean there’s a sin in the village that requires repentance. So it was a world that had a surplus of meaning. A lot of your troubles were to do with how much everything meant. Everything meant something and nothing meant nothing.

Your life meant something because you had been assigned a role that you were required to play out. The play, if you can use that metaphor, started before you arrived and it would continue after you died, and your role in the play was to be an extra. You weren’t cast on centre stage, you didn’t have any participation in the script, but your identity (and you would never have used that word) was what had been assigned to you. You needed to stand in the spot that had been assigned without complaining or arguing for the good of the whole.

If they’re the sources of the self—that’s how you’re constructed—what’s it like to be that person? You might want to think about the 500-year-ago version of you for a moment. I’ve got a few thoughts.

I reckon compared to the you now, you would know more what it feels like to be afraid. The world was a threat to you. You probably weren’t an environmentalist, because nature was mainly trying to kill you [Laughter]. Death was present. God was, in a sense, not someone who you decided to believe in, but someone whose reality was not so much just a choice as a given, like breathing. You almost couldn’t imagine the version of you or your culture that didn’t believe in God, because belief in him and evidence of him was everywhere, and self-evident. You would feel guilty and ashamed of the things that you did wrong. But you would rarely feel anxiety, and it would never occur to you that your life might not have any meaning.

You (in 2024)

Fast forward to the 2024 version of you, 500 years later. How are we put together now, compared to then? I’ll take another shot and I’m pitching for recognition.

You’re probably born into a family of one, two, maybe three siblings. Four, and someone somewhere has gone a bit crazy [Laughter]. It’s possible to have got to 30 without having seen a dead body, or even attended a funeral. Death is off-screen and hidden.

The chances that you will do with your life what your parents did with their lives are small, because your whole education has encouraged you to pursue your dreams and do what is meaningful for you. Your parents—especially if they’re Caucasian—will consider themselves to have been good parents if they encouraged you to find your own place in the world—to not do the same job as them. In addition, if you do the same job as them, they’re slightly embarrassed at dinner parties, and they explain to their friends that, “Oh, he really wanted to do it. He made that choice himself.” [Laughter]

If life is a play, you’ve been encouraged to occupy the centre stage—to be the protagonist in your story and to write your own part, because a part that’s been assigned to you by someone else will be unsatisfactory and inauthentic. Gender will have had a pretty low relevance to the kinds of career you chose. And from age 16 to 21, you’ll be sick to death of the question, “So what are you going to do when you grow up?”

Almost all the major decisions in your life—the things that are sources of the self—where you study; what you do; who you marry; which, if any, faith you follow; how you perform your gender—are all your decisions. Almost every book, every movie and every song you know is not about coping with givens, but about navigating choice. People in life with chronic situations that don’t get fixed seem to just disappear; you don’t know what happened to them, but you don’t see them around much anymore.

Your world is disenchanted. Even if you technically, as I do, believe in spirits and demons, you can go days/weeks/months/even a whole lifetime without being able to name a single event that you’re certain was caused by a spirit or a demon.

You may have lived alone, and you will probably will one day live alone. Your friends will mainly be your peers, and you will instantly recognise the experience of loneliness.

Your world has a deficit of meaning. Vast numbers of things—thunderstorms, droughts, economic events—probably have no meaning. At several points in your life, you will wonder whether anything in your life means anything at all. Almost everything you are comes from decisions that you have made.

What’s it like to be that person? You’re almost never afraid—in the sense that you could relax on Friday night by watching a horror film about literal demons to unwind from the week. [Laughter] If you believe in God, you’re aware that you do. Even if you believe the exact same creed as humans 500 years before you did, you’re conscious that, in some sense, you’ve chosen that. In addition, here’s the thing: you can imagine the version of you who doesn’t believe in that. The alternative view that doesn’t believe in God is a fairly easily imagined individual.

You’re not afraid, in terms of demons and spirits. But you are extremely anxious, because you’re worried that you’ve made the wrong choices. You feel the crushing weight of the possibility that because everything was your choice, everything in life is also your fault. That’s the way it plays out, and that’s the way we’ve come to think about ourselves.

Here’s a table summary of some of the differences:

| YOU in 1524 | YOU in 2024 | |

|

Family |

Large |

Small |

|

Death |

Present |

Hidden |

|

Community |

Strong, tight, potentially suffocating |

Weak, loose, easily escapable |

|

Your work |

What your parents did; conditioned by your gender |

What you’ve decided to do; much less conditioned by gender |

|

Freedom of choice |

Almost non-existent |

Almost overwhelming |

|

The natural world |

Full of meaning |

Absent of meaning |

|

Common negative emotions |

Fear, guilt |

Anxiety, lack of purpose |

|

Your identity |

Chosen for you |

Chosen by you |

“Expressive individualism …”

Let’s come at this from another angle. I wanted to think with you and ask you to help me exegete a picture. Mark Sayers4 points this out—that once you see it, you can’t unsee it, because it is literally everywhere. It is the picture in a thousand different guises of a woman on a mountain top with a backpack, looking at a sunrise.5 I just want to take a moment, and maybe if you’re online, you could think this out in your group or by yourself. But I’ll ask the audience here and I’ll repeat their answers back into the microphone: tell me what you see. We’re doing a bit of exegesis together—not of a text, but of a picture. What is that picture? What do you see?

Attendee 1: An ad for Kathmandu.

RS:An ad for Kathmandu. That may well be the case! I can’t remember where it was harvested from.

Attendee 2: Possibility.

RS: Yeah, possibility. If you’re looking out over a mountain and it’s sunrise, there’s possibility.

Attendee 3: Freedom.

RS: Freedom. Yeah, that’s absolutely right. This is someone who’s free—who’s unconstrained.

Attendee 4: Adventure.

RS: Adventure. That’s right: the backpack. There’s some sort of adventure. Someone’s decided to do something fun.

Attendee 5: A-communal.

RS: Yeah, a-communal: there are no people around her.

Attendee 6: It’s a woman.

RS: Yeah. I think the gender is significant: there’s a version of this from the 19 th century of the Grand Tour—Byron and that kind of figure—who was always male. This picture is almost always female. I think that’s probably significant.

Attendee 7: Accomplishment.

RS: Yeah, accomplishment. They’ve done something and they’ve done something (and I don’t meant this in the pejorative sense) for themselves. There’s no advantage bestowed on the community. There’s a very strong Eat, Pray, Love vibe here.

Attendee 8: The idea of conquest over nature.

RS: Yeah, conquest. It’s interesting, isn’t it: there’s a kind of a conquest idea. Again, it’s slightly different from the Victorian picture of the male figure out on the Grand Tour. But there is some sense of someone, having made a decision, and conquered a mountain.

A couple more?

Attendee 9: She’s been enabled by great gear. [Laughter]

RS: Yeah, okay, she’s been enabled by great gear. I don’t know whether that’s a planted advertising thing, but yeah, it is great gear. It’s also worth remembering that once you step outside the fantasy, there’s also some poor sap there who’s been told to get the angle right and, so on.

Attendee 10: Encouraging risk-taking.

RS: Encouraging risk-taking. Yeah, that’s right: it’s a situation in which there’s a certain degree of risk and possibility. Absolutely.

Attendee 11: Us. It’s really involved. I see that really obviously.

RS: Oh yeah, that’s right. This is the thing: once you’ve seen this, you can’t unsee it. It’s just everywhere. It’s like an icon of 2024 life.

We’ll have one more.

Attendee 12: It’s like a commitment to go and do it with her. She’s got up early—before sunrise. She’s gotten up at 3 in the morning to do this or something like that.

RS: Yeah, I think that’s part of it: it’s not someone who’s living in what Charles Taylor would call “sacred time”: it’s not morning and evening prayer. It’s not a communal feeling. It’s someone who’s made an independent decision to get up before dawn, go up in the dark and be there herself.

Attendee 13: It’s the freedom of wealth to do something like that as well. It’s free time to do something like that.

RS: Yes, yes. So there’s kind of a flex there of someone who’s chosen to do what they could do. Again, that’s a privilege only bestowed on men in the 19 th century as they did their Grand Tours—Byron. But here is a woman.

I think we’ve got it all. Right? Unconstrained by her community, undefined by the people around her or the roles she occupies in her community, she has climbed a mountain.

I think if we look at this picture, we assume that in some sense, she is finding herself—that she’s made a decision to get in touch with who she is, whereas any time up until about the 1960s, she would appear to most humans as lost—as someone who couldn’t possibly know who she is, because she’s been abstracted from the community that gives her meaning. Most humans would read that as a picture of lostness; we immediately understand it to be a picture of someone who is finding herself.

Second bit of art integration. Here’s a very interesting and difficult prospect: how do you persuade someone to join the army? Think about that. That’s high stakes. Baked into the whole deal that you might kill or be killed. That’s about as hardcore as it gets. Kill or be killed. Joining the army takes some persuading. How would you do that?

Here’s the next picture for your exegesis. This is from 1914:

Note the persuasive work: how are we being persuaded here to put our lives on the line? I’ll read it out: “Come into the ranks and fight for your King and Country. Don’t stay in the crowd and stare. You are wanted at the front. Enlist today.” What do you see?

Attendee 14: Get on board. Be a part of your community and don’t be a wuss.

RS: Yeah, so there’s a get on board. I mean this in the morally neutral sense of the word, but it’s appealing to a sense of shame—that is, shame is the experience of your peers thinking less of you. It appeals to a sense of shame, because you’ll be left, and that’s shameful. Anything else?

Attendee 15: It’s all about “Do it for your king and country”. There’s no [Inaudible].

RS: Yeah, so do it for your king and country. The technical word for this is an “appeal to transcendence”—an appeal to something that is bigger than you—that is larger than you. So the appeal is, “Hey, don’t think about you; think about a thing that’s bigger that transcends you and your situation.” Right, one more?

Attendee 16: A contrast between activity and inactivity.

RS: Yeah, activity and inactivity: so you’re either standing and staring, or going and doing something. So do something; don’t just stand there. Fantastic!

Let’s go to the next one. This is a 2024 ad:

Attendee 17: It’s a woman.

RS: Interesting, right? I’ll stop getting you to do the lecture for me. But immediately, I think, again, gender is probably relevant to the picture. It’s a person by themselves. The appeal is to “Do what you love”—that is, in our categories, to think about the army as the platform on which you could enact your play and bring your script into the army to enact your play there.

Just in case you missed it, they italicised the word “you”, which is kind of amazing. That is a picture of what Charles Taylor calls “expressive individualism”. How do we construct our modern selves? Taylor says we are expressive individuals: we find ourselves by an inward journey, rather than a communal journey. You climb up a mountain; you decide to join the army to play out a particular narrative. That’s the individual aspect.

“in an age of authenticity …”

Then your moral obligation, having discovered that identity, is to then express that to the world. Our obligation as fellow citizens is to receive your expression, to validate that and to take that on. We’re, as Taylor says, expressive individuals in an “age of authenticity” in the post-60s cultural revolution in which authenticity—that is, not merely accepting the role that was assigned to you, but forging your own way as essential to the good life.

Authentic identity as salvation story

Finally, and this is the end of the descriptive bit and you might have picked up on this already, expressive individualism comes kind of in the form of a salvation story. If you’re a Christian and you think in categories of Creation, Fall, Redemption and New Creation, you’ll notice that expressive individualism has a similar structure:

| Origins | Fall | Hero | Denouement | |

|

The expressive individualist salvation story |

There is a true self inside me. |

Through external forces that self was lost/pushed aside. |

I was liberated to rediscover that true inner self through a person/event. |

I am still working through it and facing conflict, but things are materially different. |

The way it plays out in films, books and popular music is that there’s a true self. That’s the origin story. In the Fall, I’ve become alienated from that true self: something’s disrupted that harmony of the original creation. These external forces have made that a hostile experience. That’s a hero moment where you’re liberated, and through some sort of circumstance or crisis or human, you reconnect with that true inner self and the circumstances now—the testimony—is that you’re still working on it, facing some conflict and so on, but things are materially different, having gone through that crisis and got in touch with your original and true self.

Again, high marks if I’ve described something that sounds familiar, and my bad if I haven’t.

2. Modern identity construction: So how’s that working out for you?

My second task is evaluation. That was my attempt at a fairly impartial description of expressive individualism. You may be shocked to find that I have some criticisms of it. However, I’m going to completely evacuate the room of all energy and bring in a word that kills political and online discussions by introducing nuance [Laughter]. That is, I think the answer to the question, “Is expressive individualism good or bad?” is (and watch the energy go) “It’s complicated.” [Laughter]

Here’s a few reasons why I think it’s complicated.

Revealed vs stated preferences

Firstly, in economics, economists distinguish between “revealed” and “stated” preferences. Stated preferences are the ones we think we have, and revealed preferences are the ones we actually have. Before Netflix went online, everyone claimed they were into arthouse and indie films; as soon as Netflix went online, we just want to watch reality television and Will Ferrell films. [Laughter] Or in the airline industry, if you ask people right up until deregulation what they wanted, they said they wanted the full service with food and lots of legroom. It turns out what we actually want is no legroom, terrible seats, no food and a cheap fare.

In the same way, I think you almost never meet someone who’s an enthusiastic expressive individualist. You almost never meet anyone who says, “Oh, this is the good life. This is the way it’s done.” And yet it is what we consistently choose. Think about migration patterns: that’s a very high-stakes thing. By the time you’ve moved your family from X to Y, migration patterns are almost always from less freedom to more freedom—almost always from rural to urban, which is a kind of proxy vote for having more freedom about establishing your identity. That’s the way urban centres work: they give you the freedom that rural centres do not.

The self arising from Christianity and the Reformation

Secondly, the other complication or one of a few is that you couldn’t understand this way of constructing the self apart from Christianity in general and the Protestant Reformation in particular. You want to bake that into any harsh criticisms of the way we put ourselves together—that whether it’s an own goal or a wonderful fruit, it is, at least partly, the product of the way that Christianity in general understands individuals and the way the Reformation in particular made it possible for someone to somehow dislodge from their nationality, family and geographic location—that those things ought not be the last word on who you are. So one of the complications and nuances is that we’re telling as Christians a kind of family story.

Criticisms

But I have got a few criticisms.

i) New and novel

Really quickly, it’s just really new. This way of thinking about how to put yourself together is super new. It’s kind of a post-60s thing and that I think that, on its own, should raise some red flags.

ii) Underthought and under-tested

It should raise some red flags because things that are new are often under-thought. Because this way of putting yourself together is so ubiquitous, we assume that someone somewhere has done the hard thinking to work out whether it’s coherent. But I think the truth is that it’s very underthought. The emperor, if not completely naked, is at least taking a dash for the bathroom and has grabbed what he thought was a towel, but it turned out to be a flannel [Laughter], and we’re all hoping he doesn’t trip over [Laughter].

Some of them are so obvious, it’s almost embarrassing. For example, how are we deciding on these true selves? Which true self is the one that you’re privileging? Which is the one that you’re hiding from the rest of us? On what criteria are you making these decisions? On what basis have you decided this part of yourself is authentic and this other part is completely extraneous to who you really are?

Second one that’s super obvious: who decided that I was best positioned to answer who I am? My qualifications are immediately brought into suspicion by the fact that I don’t even recognise my voice when it’s on a voice recorder [Laughter]—that the moment I hear it, I say, “That’s not what I sound like!” [Laughter]. My voice has once been described as like a chipmunk with an Australian accent [Laughter]. You know that is what I sound like! [Laughter] So at one point did we decide that the guy who doesn’t even know what he sounds like is the infallible last word on who I am?

One of the liberations of the Christian doctrine of the judgement of God is that it tempers our ability to judge ourselves. The Apostle Paul opens up the first-century version of the Johari Window, where he says in 1 Corinthians 4:3-4, “I do not even judge myself. My conscience is clear, but that does not make me innocent. It is the Lord who judges me.” Part of Christian identity is a little bit of circumspect judgement of our own judgement of who we are.

The other one that is obvious—and I don’t want to be misunderstood on this—is if we’re finding ourselves alone, why do those selves end up being so similar? If those selves are forged in the deep isolation of Mount Doom, why do they need all this community validation? If the true self is unique and self-discovered, why do we need communities to express them?

I don’t say that in judgement of other communities; I say it as a truth about my community. I’m a Christian, and just as people of certain sexual orientations or gender expressions find others, that’s exactly what I’ve done. Having become a Christian, I’ve found a group of people—a church—with whom I can work out who I am based on this kind of shared identity.

But why does that happen? My criticism is not doing that, which is I think is vital to any sense of identity—to any coherent answer to the question, “Who am I?” My critique is just that expressive individualism doesn’t have a good reason for why we do that. I think the Scriptures do.

iii) Poor outcomes

Two other criticisms: thirdly, the poor mental health outcomes. One of the easy ways to identify this is to describe expressive individualism to someone and ask, “So how’s that going for you?” The anxiety, fragility and crushing sense of aloneness and meaninglessness are very bracing.

iv) An alternative gospel

Finally as Christians (or me, at least, as a Christian), I notice that expressive individualism comes to us a kind of a competitor to the gospel. It is shaped like a salvation story, and comes to us as a rival to the gospel. The traffic from the church is not toward Islam, Buddhism or Hinduism. If your church is smaller than it was, that’s not where they’ve gone. They’ve gone to a kind of general secularism that is undergirded by a sense of expressive individualism. It’s an alternative to the gospel.

Maybe even more insidiously, it comes into the church in a kind of moralistic, therapeutic deism as the gospel—that we are centre stage and that Jesus is, in some sense, the one who allows me to come to my full expression at centre stage as the kind of person that I always was meant to be.

3. “Find your Identity in Christ”: Problems and possibilities

This is the shocking turn, so brace yourselves! It’s like one of those old Buzzfeed articles: “Number 3 will shock you!” We’re at the point where we talk about finding your identity in Christ—finding yourself in Christ—and the answer feels like, “Is that what we should do?” Obviously, yes! That’s the solution: find your identity in Christ. Is that true? I want to say, “Yes”, “No” and “Sort of”.

Identity and salvation in Christ

Firstly at some basic level, yes. The Bible doesn’t use identity language: that word is new, but if you know how to read the Bible, you don’t need the word there to tell you that the concept is there. If you did a word study on “love”, you won’t find the Prodigal Son story, and if the Prodigal Son is not part of how you understand love, that’s a really weird thing. I think it would be weird to say that the Bible doesn’t have something to say about what we call “identity”.

From the very first, when Christianity launches onto the world, it creates identity crises wherever it goes. It’s an identity crisis for Israel. It’s an identity crisis for the Gentiles and their relationship to Israel. It creates a crisis for Roman citizens, single virgins and slave-owning masters.

The New Testament language is easily recognised as some kind of identity language. We’re “in Christ”. We’re united with him (1 Cor 6:17). We’re one with him (1 Cor 6:17). We’ve put off our old self and we’re being renewed into a new self (Eph 4:22-23). Paul says, “I no longer live, but Christ lives in me” (Gal 2:20). So there is some sense where identity in Christ is not something we bring to the Bible, but something we find in it.

But here are my cautions. The word is not there, and it may be that in that word, we bring some freight with us. Again, in Nathan Campbell’s article in Zadok, he talks about this—that there may be a kind of Trojan Horse situation to watch there—that when we use the word “identity”, we’re bringing more into the city than we first anticipated.

Secondly, it accepts the premise that the question is right and the solution is wrong. If our world says, “Find your identity in x, y or z” and we say, “No, find your identity in Christ,” at that point, we’ve just swapped out the nouns. The noun of your nationality, we’ve swapped that with Christ. We haven’t said much more than that, so therefore, we haven’t questioned whether the methodology is valid—whether the search, framed that way, is actually one that we’re going to set ourselves up to win. I think the tell phrase here is when we talk about “I identity as a Christian”. I think at that point, something has been smuggled into the Scriptures.

I want to ask, thirdly, a pastor’s question: how robust is that in the trenches of pastoral care? How is that high definition enough as a concept to do the kind of help that we sometimes think it will? One of the young adults is discovering and struggling with a sense of same-sex attraction, and we might say to them that they ought to find their identity in Christ. But we wouldn’t tell the mother, having miscarried, that her grief is evidence of that her identity was in motherhood and not in Christ. There’s something going on there that’s just a bit more complicated than the way we sometimes present it.

Colossians 3-4:1 and identity formation

I thought to finish, we’d do something fully crazy and do a little Bible Study. Rather than jumping all over the place, let’s settle down as we finish into Colossians 3 as we try to see what the Bible does say about these things.

Notice both the radical and conservative nature of this passage:

Since, then, you have been raised with Christ, set your hearts on things above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things above, not on earthly things. For you died, and your life is now hidden with Christ in God. When Christ, who is your life, appears, then you also will appear with him in glory. (Col 3:1-4)

There’s something about identity there, right? The person has encountered Christ and has experienced in him some radical transition about where they are—about where their self is. They’re hidden with Christ in God. Their life will appear with him, because it’s hidden with God.

Also, there’s a radical kind of recasting of what we would call “identity”:

… and have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge in the image of its Creator. Here there is no Gentile or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free, but Christ is all, and is in all. (Col 3:10-11)

It’s kind of wild. There’s this new self that we put on. By putting on that new self—by being in Christ, by being united to him (here’s where it’s worth paying attention)—we enter into a “here”, which, I take it to be, the church. “Here” in Christ, among his people, we enter into this space in which our previous ethnic identities (Gentile or Jew), religious identities (circumcised or uncircumcised), cultural identities (barbarian or Scythian), socioeconomic identities (slave or free) are all swept away here, because Christ is “all” and is “in all”.

But notice alongside that, there’s a moral imperative. There’s descriptive language: it’s a statement of what you are—not a chosen identity, but an identity that is given to you. But the moral imperatives involve a kind of acting out—a kind of “dressing up”, a cosplay, a form of what CS Lewis calls in Mere Christianity “Let’s pretend”, which is kind of dissonant language in the age of authenticity. But I think here, part of the form of the moral life—part of the way you find your identity in Christ—is not to be drawn on an inner journey, but to cosplay an identity that has been received as being, or at least is giving a crack at being, compassionate, kind, humble, gentle and patient (Col 3:12). It’s different.

The modern construction of self-discovery involves spontaneity. It’s interior and inward-directed. But this form of identifying with Christ and in him has much more space for putting on and trying out. It’s got a kind of moral rote learning. It sounds more like the humble inauthenticity that comes, at least in the early stages, as you try to learn a new language, and your face has got that kind of pensive look as you try to conjugate the verb and worry that you’ve said a word that might either mean “mum” or “you’re dead to me”.

Or it’s like learning a new dance in which you’re awkwardly not indwelling the form, because you’re thinking, “One, two, three four; one, two, three, four” as you look inauthentic ahead of anything becoming really natural.

Notice the way that the New Testament owns the formative power of community. I think in the Bible, the community of the church is not the fruit—the reward you get at the end of self-discovery that happened in isolation. But it is itself the source and the (to use a modern word) lived experience of working your way into Christ—of being part of a community where you see in others what you’re meant to be.

This is where the Bible does things that we find embarrassing, such as inviting imitation—saying to Christian leaders, “One thing you can do is be more like them.” Imitate them. Be part of a community where you can mimic one another—where you can get together like in a language course and practise not lying. Let’s give that a crack! Be in a community where you have a go at forgiving each other and teaching and admonishing one another. In addition, often by rote and against instinct, practise receiving one another across cultural and economic barriers as fellow selves in Christ.

Notice, finally, the conservative force of creation alongside the newness and radicalism of the new creation in Christ. Sometimes we speak about identity as cut from whole cloth—as this kind of “Year Zero” approach, where the “before” and “after” of life in Christ is dramatic: we come a kind of Rousseau’s jungle—a kind of blank canvas on which Christ imprints a new identity. Certainly here, there is “no Gentile or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised” (Col 3:11), because we have been overwhelmed in Christ. Yet from verse 17 on, there are in Christ, husbands and wives, fathers and children, and masters and servants—pre-existing realities that get dragged into this new situation and continue to exert their obligations and duties on us, even though and because, we have been united to Christ. I think the tell here is the language of being “renewed in knowledge in the image of its Creator” (Col 3:10), which is both radical newness, but also harking back to our original purpose of bearing the image of God in the world (Gen 1:27).

Conclusions

Matthew Anderson argues in a 2012 essay that we might be better served by the more concrete language of the New Testament.6 I think “finding your identity in Christ” is essentially true, but it’s a kind of abstraction. The question is, “How do you do that?” You do that in the concrete. It’s not by being identified as a Christian or being identified in Christ, but by “Trying this on”—being a disciple of Christ, a child of God, a brother or sister within the community, or, in the traditional baptismal liturgy, a “soldier of Christ Jesus”. These sources of the new self bring with them the duties and obligations—without with, we will never be truly and authentically those who have been found in Christ.

Thank you.

[Applause]

Advertisements

PO: Brilliant. Thank you very much, Rory! Just a few announcements.

CCL podcast

The podcast comes out every couple of weeks. It’s on various issues and contains interviews. You might find that helpful.

On the CCL website, there’s also a podcast survey. If you listen to the podcast, we would love to have your input on how we can improve the podcast.

Support CCL

We would love it if you would prayerfully consider making a donation to fund the Centre for Christian Living. That would help us with our overheads.

Conclusion

PO: Join me in thanking Rory for his time tonight. Thank you, Rory!

[Applause]

I will close our evening in prayer.

Our heavenly Father,

We thank you so much for Rory’s hard work in preparing this evening, stimulating us, helping us, pointing us to your word, and helping us to think about who we are.

Father, we pray that you would continue to give us clarity. Help us to think about ourselves truly and honestly in light of you and your word, and help us as we minister to others to help them to think about themselves truly and honestly in light of your word, and in light of Christ.

We ask it in his name. Amen.

[Music]

PO: To benefit from more resources from the Centre for Christian Living, please visit ccl.moore.edu.au, where you’ll find a host of resources, including past podcast episodes, videos from our live events and articles published through the Centre. We’d love for you to subscribe to our podcast and for you to leave us a review so more people can discover our resources.

On our website, we also have an opportunity for you to make a tax deductible donation to support the ongoing work of the Centre.

We always benefit from receiving questions and feedback from our listeners, so if you’d like to get in touch, you can email us at [email protected].

As always, I would like to thank Moore College for its support of the Centre for Christian Living, and to thank to my assistant, Karen Beilharz, for her work in editing and transcribing the episodes. The music for our podcast was generously provided by James West.

[Music]

Endnotes

1 Nathan Campbell, “Identity as a Trojan Horse”, Zadok Perspectives 161 (2023): 8. https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/informit.451763667372501.

2 It’s not a Bible word, though the concept might be there.

3 Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989).

4 Mark Sayers, The Vertical Self: How Biblical Faith can Help Us Discover Who We are in an Age of Sel-Obsession (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010).

5 Rory says “sunset” in the recording, but corrects himself later.

6 Matthew Lee Anderson, “The Trouble with Talking about our ‘Identity in Christ’”, Mere Orthodoxy (blog), 12 July 2012, https://mereorthodoxy.com/trouble-with-talking-about-our-identity-in-christ.

Bible quotations are also from THE HOLY BIBLE: NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by International Bible Society, www.ibs.org. All rights reserved worldwide.