In an age when authenticity, personal potential and the fulfilment of that potential is so highly valued, the virtue of self-control seems counterintuitive. In contrast to the world, the Bible tells us that the good life is not located in unbounded self-expression, but in purposeful self-restraint.

Why is self-control so necessary to the Christian life? What does the Bible say about it, and how can we cultivate it within ourselves? Furthermore, does the deliberate curbing of desire really play a key role in our self-actualisation?

In this episode, we bring you a recording of our recent event in our series on virtue in the Christian life in which Moore College lecturer David Höhne helps us think through how to live as Christians, living self-controlled lives in a world that so values self-actualisation.

Links referred to:

- Watch: Self-control in an era of self-actualisation

- 2021 Annual Moore College Lectures: “In him all things hold together: The triune God and the choosing self” by David Höhne

- Our October event: The power and pain of perseverance with Mark Thompson (Wednesday 18 October 2023)

- Support the work of the Centre

- Contact the Centre about your ethical questions

Runtime: 55:09 min.

Transcript

Please note: This transcript has been edited for readability.

Introduction

Peter Orr: This year in the Centre for Christian Living events at Moore College, we’ve been thinking about the virtues of the Christian life. One of the key virtues that Peter mentions in his virtue list at the beginning of his second letter is self-control (2 Pet 1:6). Paul also mentions self-control as the fruit of the Spirit (Gal 5:22). However, self-control conflicts with one of the values that our modern world holds to: the idea of self-actualisation—being true to who you are.

In today’s episode, we have a recording of our recent event where David Höhne helps us to think through how to live as Christians living self-controlled lives in a world that so values self-actualisation. I hope you enjoy today’s episode.

[Music]

PO: Good evening and welcome to our event at the Centre for Christian Living. My name is Peter Orr, and if you’re a regular at these events, you’ll know that normally Chase Kuhn is standing here, introducing the evenings. Well, Chase is on six month’s research leave, working on a book on the Christian life and ethics. Hopefully at a future evening, we can enjoy the fruit of his research. I’m very glad to be here with you this evening to welcome you. If you’re watching online, welcome to you. I’m very much looking forward to this evening.

The Centre for Christian Living is a centre of Moore College that exists to bring biblical ethics to everyday issues. This year, we’ve dedicated our four live events to exploring the idea of a virtuous life. In Peter’s second letter, he encourages believers to make every effort to supplement their faith with virtue. The virtue we’re going to think about this evening is the virtue of self-control and how that relates to a world that seems so obsessed with the idea of being true to yourself.

This evening, we have our speaker David Höhne, Moore College lecturer, Academic Dean and friend of mine. David is the author of a number of booksm and in 2021, he delivered the Annual Moore College Lectures on the title of “In him all things hold together: The triune God and the choosing self”. David and Amelia attend St Stephen’s Anglican Church in Newtown, and I believe there are some friends from St Stephen’s here this evening.

As I said, we’re thrilled to have you here in person and online. Our plan this evening is that we’ll begin by hearing from David on our topic, and then afterwards, we’re going to have a conversation between two of our student team, thinking through some of the practical implications of the presentation for our lives as Christians. Then finally, we’ll finish with a time for question and answer.

I’m going to read the Bible and then pray, then David will come and address us. This is the passage that’s been the focus of our series this year:

May grace and peace be multiplied to you in the knowledge of God and of Jesus our Lord.

His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence, by which he has granted to us his precious and very great promises, so that through them you may become partakers of the divine nature, having escaped from the corruption that is in the world because of sinful desire. For this very reason, make every effort to supplement your faith with virtue, and virtue with knowledge, and knowledge with self-control, and self-control with steadfastness, and steadfastness with godliness, and godliness with brotherly affection, and brotherly affection with love. For if these qualities are yours and are increasing, they keep you from being ineffective or unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. (2 Peter 1:2-8 ESV)

Let’s pray.

Our Father,

We thank you for this evening. We thank you that we can meet together or be online, and think through this important topic. We pray for David as he helps us to think through what it means to be self-controlled in a world that does not seem interested in that. Please give us clarity, and please, as a result, would we be resolved to live evermore for the Lord Jesus.

We ask it in Jesus’ name. Amen.

Please join me in welcoming David.

[Applause]

Part 1: Self-control in an age of self-actualisation

David Höhne: Thank you very much, everyone. It’s great to be here with you. I must take the opportunity to be thankful that there are so many bodies in the room. Peter mentioned the Annual Moore College Lectures that I delivered in 2021. If you had a cold during 2021, you probably weren’t alone in the world. I was, however, alone in this room with Daniel and the camera for six days a couple of hours at a time. So it’s nice to see real people here. Apart from Daniel; it’s always nice to see Daniel! It’s nice to have some more friends.

1. Introduction

a) Words of the wise on self-control

Self-control in an age of self-actualisation. You can see on the screen the words of the philosopher Aristotle, spoken or written around 500 years before the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth. I’ve included them just to highlight the fact that Christians aren’t the only ones for whom self-control is either an issue or perceived to be a benefit. Aristotle writes, “I count him braver who overcomes his desires than him who conquers his enemies; for the hardest victory is over self”.1

Nearly 2,500 years after Aristotle and 1800 years after the ascension of the Lord Jesus, Jane Austen was just as interested in self-control. She writes not long after the sunrise of the European Enlightenment—not long after the dawn of a new era of self-actualisation for individuals in Western culture: “I will be calm, I will be mistress of myself.”2 (I’m not sure if it was the Sensible or the Sensibility one who says that. I’m thinking it’s the Sensible one.)

Tonight we’ll reflect on the way that Christians engage in self-control to see what makes it a distinctly Christian virtue in an area that acclaims and proclaims self-actualisation as the highest good for individuals in society. You can see some of the words of the Apostle Peter that the lecturer Peter just read out:

For this very reason, make every effort to supplement your faith with virtue, and virtue with knowledge, and knowledge with self-control, and self-control with steadfastness, and steadfastness with godliness … (2 Pet 1:5-6)

Let’s begin by clarifying some of the terms that will be used tonight. Firstly, following philosophers like Alasdair Macintyre, Charles Taylor and Kathleen Wallace, I will refer to the self as a network of interlocking and overlapping relationships. From this perspective, self-control could be thought of as the effort it takes simply to achieve some kind of coherence or integration as a person. “Keeping myself together” is a baseline form of self-control.

Secondly, however, and certainly from a classical point of view (as we observed in Aristotle), self-control refers to “restraining one’s emotions, impulses or desires”. It was already considered to be a virtue at the time the New Testament was written. In the New Testament, the language of self-discipline or rational self-assessment can sometimes be translated into English as “self-control”. You’ll see “self-control” appear in a number of Paul’s letters, but the specific Greek word for “self-control” may not be there. The concept, though, is close enough for the translators to refer to, as I say, “rational self-assessment” or even “self-discipline” as “self-control”.

Taken together, these ideas present us with a portrait. Broadly speaking, self-control in the New Testament is a portrait of mind and body being guided and governed by the self towards a certain goal, and away from opportunities to compromise that goal.

With these things in mind, let’s turn our attention to the concept of self-actualisation.

b) The network self to be controlled

Usually in our modern parlance, the modern self is usually either a matter of consciousness, from the writings of Descartes, or pure consciousness, according to John Locke. The main modern alternative is the animalist or organicist approach, where the self is exclusively some kind of biological organism. The feminist philosopher Kathleen Wallace refers to these as “container” frameworks:3 the body is either the container of cognition or a collection of bodily functions. They are essentialist philosophies seeking to determine “the thing” that the self “is”. In contrast, philosophers like Wallace propose that we think of the self in more network terms. The modern self is more likely to consider social, cultural or interpersonal traits as an obstacle to self-hood These are accidents in the pure sense, with the “real” self being refined to some kind of biology, the exercise of pure reason or my willpower. These are the “real” self—that is, me.

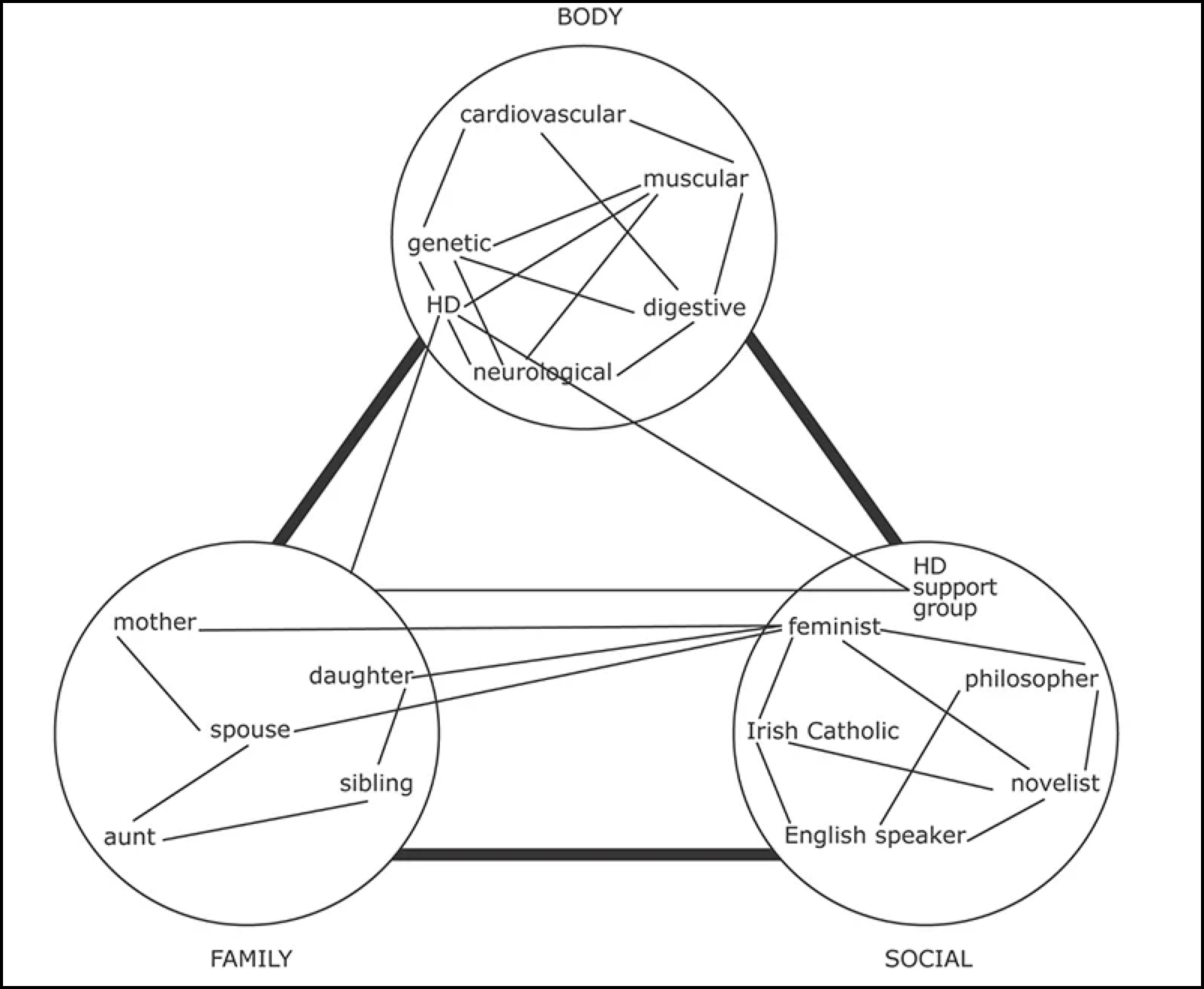

However, the “network self” acknowledges social embeddedness, relatedness and intersectionality as being fundamental to what makes up a self. Wallace’s diagram includes body, familial relations and a larger social network, and Wallace’s theory and communitarian philosophers like her want us to keep in mind that the self is actually a network of interactions and relationships.4

Let’s take a concrete example—one suggested by Wallace. Consider Lindsey: she is spouse, mother, novelist, English speaker, Irish Catholic, feminist, professor of philosophy, automobile driver, psychological organism, introverted, fearful of heights, left-handed, carrier of Huntington’s disease (HD), resident of New York. This is not an exhaustive set; just a selection of traits or identities that make up her network self. Traits are related to one another to form a network. Lindsey is an inclusive network, a plurality of traits related to one another. The overall character—the integrity or the self that needs controlling—is constituted by the unique interrelatedness of these particular traits, whether they be psychological, social, political, cultural or linguistic.

Lindsey will aspire to have a holistic experience of this network identity. At a baseline, keeping that fabric together is part of self-control. This will result in major or minor identities, depending on how disparate the contexts in which the relations take place are from each other. Some relations may not always be determined by the network of relations, since the context may change: Lindsey will always be a daughter and potentially always a mother, but not always an automobile driver and not always a professor of philosophy. So she sees herself as changing as a consequence over time.

2. Self-actualisation in modern culture

In Western culture, there have been significant social and cultural pressures on the network self. We are going to consider two of those—Romanticism and free market capitalism—as the main social drivers that push this network towards self-actualisation in the midst of its attempts to control itself.

a) The Romantic self

Turning to the first driver—that is, the influence of Romanticism in Western culture. Nikolas Kompridis has suggested that there are five characteristics to Romanticism:5 the fact that Romantics long for freedom through new beginnings; they experience that freedom as self-determination through self-expression; and the primary form of self-actualisation was through art. The Romantics drew energy for their inspiration through a deep reverence for nature. Finally, despite what appears to be an affection for the transcendent, the Romantics looked for the living force of things in authentic experiences of the everyday.

Now of those five interacting characteristics, we’re going to focus on self-actualisation in Romantic thought.

i. The genius

For 18th and 19th-century Europe, the era of political, industrial and scientific revolution inspired Romantics to search for a very modern view of the self. Instead of the largely mechanistic models of self and nature, which saw the self or nature as being like a machine, the Romantics revered the rugged individualist, and ultimately the “genius”.6 Think of Beethoven, for example.

Learning and education are worthy pursuits, but the genius inspires us, because he is truly original in line with the Romantic desire for new beginnings. The genius is the one who starts new beginnings in our culture. They have imagination unbounded, but also the ability to mediate genius to us through their art. In this way, they capture some of the living force of things and make it available to us as well. In fact, Tim Blanning points out that the 18th century saw the emergence of a cult of genius, as the heroic figure not only stepped out beyond his peers, but also drew all society along with him.7 Hence we get the “Great Man” view of history.

As Robert Richards has shown, in Romantic terms, the genius had an innate ability to feel or intuit his way towards the creation of beauty, and in so doing, establish the means by which human freedom could triumph over an otherwise deterministic machine-like world.8 This significance of this ability goes far beyond the poetry and paintings with which Romantics are associated by the likes of, say, Carl Trueman, or even Charles Taylor. The Romantics desired not just self-expression, but a process of self-actualisation as the means of achieving overall self-determination. The unique self was the genius’s greatest achievement, and his greatest act of imagination and creativity.

ii. Self as Bildung

Romantics wanted the cult of genius to become the zeitgeist—the spirit of the times—the culture for everyone, as the philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder had called it. For the Romantics, the answer was a citizenry grounded in education as the highest good. To meet this challenge, they proposed a concept of the self called in German “Die Bildung”.9 “Bildung” is a compound word that means, literally, “formed image”. It was derived from the way that medieval mystics had written of God penetrating the core of an individual soul and shaping that soul in his image.

For the more secular Romantics, though, an individual’s Bildung was the harmonisation of her mind, heart, selfhood and identity through personal transformation using exacting standards of education across a wide range of sciences and arts. One’s Bildung was far more than the three “Rs”.10 The cultivated man or woman developed their Bildung as a process of self-determination in harmony with “the living force of things”. That is, when I feel that I am in my most best state of having achieved my Bildung, the whole universe is there to applaud me.

Pursuing one’s Bildung was intended to steer a course between the hedonism of bourgeois society, on the one hand, and the stoicism of rational approaches to ethics, like Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative. You can find the contemporary version of Die Bildung in the prospectus of any independent church or private school. My teaching friends tell me that every middle-class family has a gifted and talented child, and they’re all working on their Bildung at school, even as we speak.

We must appreciate the importance of this social movement as a rival to the religious concept of sanctification. What the Romantics thought they were doing is actually providing a non-Christian way of/route to sanctification. The pious self-examination of the confessional was turned to “our inner depths, to the hidden recesses of the self” for discovery in the potential of dreams, hidden fears and unspoken fantasies.11 Making my dreams come true is Romanticism at its heart.

Covering all these things is love: the Romantics sought to “awaken, nurture, and refine the power of love”.12 They did this because they considered that the Enlightenment’s championing of reason had repressed and ignored this vital aspect of humanity for too long: “The Romantics saw it as their mission to restore the sovereignty of love to the realms of morals, politics and art.”13 Beiser14 writes, an individual will gladly give themselves to a community and to the state “from the affection and devotion of love”—far more so than “the universal norms of reason”.15 When I feel love, I can change the world, and when I follow my dreams, I will feel self-love like no other.

iii. Authenticity and Bildung16

The struggle for personal liberty in such an environment made by self-determination is not at all a forgone conclusion. After all, isn’t everybody vying for self-actualisation together—somehow against one another?

The Romantics wandered in the forests or trekked through mountains, seeking new experiences and authentic expressions of old ones. The point of these quests was to achieve a sense of authentic alignment between oneself and the living force of nature—that is, to bridge the gap between my actual self and my ideal self. While an exercise in individual meaning, the goal was much more objective than the later existentialists, for whom life may well have no meaning at all, for the Romantics always sought to align themselves with the universe.

Of course, sometimes when the universe is aligned with me, I was the only one who thought so. [Laughter] But as long as I kept working at it and fulfilled my dreams, then even failing in that quest became a romantic virtue. Therefore, tragedy and melancholy become the highest of Romantic virtues—as Tim Blanning has shown.17 In fact, the glorious failure of the Romantic is encapsulated in madness and, most ironically, youthful suicide. One of the most popular books of the 18 th century was Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, which was a story about a young man committing suicide because of unrequited love. Young people “literally killing themselves” has been an almost celebrated aspect of Romantic culture since the 18th century.

The Romantic spirit of seeking authenticity: that’s our first great pressure—our first great energy—in the social network that’s affecting our network self as part of the drive for self-actualisation. The next one I would like to consider in concert with this is the power of free market capitalism and what that meant to the culture of self-actualisation.

b) Free market capitalism and the power of choice

i. The power of self-interest

According to the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, the Western Anglo-European culture entered an “Age of Authenticity” in the mid-20th century. The affluence provided by post-World War II economic recovery in the West played a significant role in evolving 19th-century Romanticism into the age of expressive individualism, as Carl Trueman has called it in his book, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self. What emerged at this point in Western culture was a marriage between the Romantic ideals and the concept of freedom inherent in free market capitalism—freedom for the constraints others and freedom to pursue self-interest.

In this context, the very notion of a “common good” is one where every individual is free to pursue that which she and her family need. Or as the philosopher Adam Smith wrote in the 18 th century,

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love.18

The rationality of this proposition is obvious. But what it not stated is that only the individual can determine what is best for her and hers. This may be redeemed if the individual is suitably grounded in the frame of family and larger society—a trope to which modern advertising returns again and again. But once the self-actualised modern self is freed from those kinds of constraints, what happens?

ii. Dreams, desires and advertising

Edward Bernays, the father of modern advertising and public relations, made particular use of his uncle Sigmund Freud’s theories concerning hidden dreams and repressed desires as the bedrock for the way advertising was meant to work in the 20 th century. That is, the experiences so vital to Romantics, like dreams, hidden desires, fears and those sorts of things, are actually being imported to the mainstream of how advertising is to work in our emerging free market economies.

In 1925, Bernays gave a speech before a group of public advocates and civic leaders where he declares, “the individual and the group are swayed by only a very small number of fundamental desires and emotions and instincts” including “sex, gregariousness, the desire to lead, the maternal and paternal instincts”.19

As César García has shown, in Bernays’s book Propaganda, he argues that the individual thinks “by means of clichés, pat words or images which stand for a whole group of ideas or experiences”.20 Bernays associates images with the power of symbols as the means for persuasion: “The acceptance of a symbol is emotional and expresses an associative mental process stemming from familiarity”.21 What all that means is if you can lock onto the right kind of image—the right kind of symbol—you can move people from their inner compulsions. This was exactly in line with the Romantic desires for self-expression and self-determination, where art is supposed to be making all those things open to the public.

Therefore, the central focus of these mental process was the self-image. In terms that would have made the hearts of German Romantics sing, Bernays focussed on the deterministic role that emotions and symbols play in human perception, especially perceptions about ourselves. Advertising, or truth in market terms, works by expressing desire, and there are few desires stronger, bigger and better than a desire for a better self. This technique became fundamental to modern advertising and the driving force of consumption that is so central to free-market economies.

iii. Consumers who buy identities

Back in 2005, economists and psychologists began using the term “affluenza” to describe what they perceived as the social and emotional effects of sustained consumption in our Western world. From our perspective, affluenza adds a number of important signs to the business of self-actualisation—namely, what Clive Hamilton and Richard Denniss call the practice of “buying an identity”.22 Hamilton and Denniss observed that psychologists speak of an inbuilt desire to align the actual self with the ideal self. We’ve already mentioned this in terms of Romantic thought—that is, the gap between who I am and who I would like to be. One of the key aspects of affluenza is the desire to bridge that gap through consumption. Affluenza is the falsehood of achieving authenticity through associating brands with my sense of self. As one CEO of Gucci said,

Luxury brands are more than the goods. The goods are secondary because first of all you buy into a brand, then you buy the products. [The brand gives] people the opportunity to live a dream.23

Consequently, people don’t mind handing out thousands of dollars for samples of that brand. No one can afford $50,000 for a dress or a suit, but you will go for $1000 or even more for a pair of sunglasses or a handbag with that same brand on it, because we associate that brand with ourselves as part of our project of self-actualisation.

iv. The self as a commodity

The power of free market capitalism to produce commodities—that is, to commodify anything and everything—has set the stage for self-actualisation to transcend mere consumption and become itself a commodity. As economists have noted,

Capitalism has an immense capacity to reduce persons, non-personal creatures, space and time all to commodities that can be efficiently traded for profit and related by contractual arrangement.24

It’s worth noting here that deciding on what is a commodity—what can be bought and sold—is always a moral decision. But what is the moral framework that is guiding and governing the decisions concerning what can be and what should not be a commodity—particularly in an environment where the actualisation of the self is the highest good? What can we expect of a moral framework that rests on self-interest and freedom from constraint when it comes to making moral decisions about what could or what ought not be offered for sale or consumed?

The advent of social media platforms have taken this to an entirely new level: through the means of various platforms, a privately generated or curated image can become a highly influential lucrative brand for public consumption. The Romantic genius has a new name: the “influencer”. Yet even if one is not considered to be one of these “influencers”, as the Cambridge Analytica scandal of the 2010s alerted the public, the ongoing way that social media platforms trade the data or their users’ identities have already, thereby, made them into commodities for training. Self-actualisation is a highly lucrative commodity: the power of the image is driven by hidden desires, but once they are transformed into an ideal, that image becomes the new drive that keeps the cycle going and growing.

c) Critiques of authenticity

You’ll be pleased to know that not everybody is happy about this. In the early 20 th century, philosophers like Theodor Adorno and others who made up the Frankfurt School criticised the Western culture of self-actualisation. Adorno complained of a “fetishisation and atomisation of the self that could drive consumer culture, on the one hand, and provide perfect subjects for irrational mass movements such as fascism, on the other”.25 That is, if the whole world is a battle of wills, then the winner is the will that exercises will over all others, which we saw in World War II.

The existentialist philosophers of the 20 th century had, in Adorno’s terms, turned the dreams of their Romantic forefathers into a culture of narcissism whose only alternative to despair was consumer culture. Not only like Nietzsche before him, though, Adorno blamed Christianity for the tendency to inwardness deep in Western culture, starting with Jesus of Nazareth and his wrestle in the desert, and subsequently developed and distorted by Augustine, Luther and Kierkegaard, just to name a few.

Adorno was correct, I think, in diagnosing the Western culture of self-actualisation as inherently narcissistic. He was also correct in seeing a thread through Christendom from the Lord through Augustine and Luther, and even onto Kierkegaard. But he was completely wrong about why they all looked to identity of the self as a key area of interest.

It was the Lord Jesus who pointed out that it’s what comes out of a person—out of the heart—that reveals what is true about them (Matt 15:17-20). That truth is an envious inward retreat from God’s sovereignty expressed in his promises concerning his chosen king. It’s the reason why Wallace’s picture of the network self has no reference to God. Did you notice that? The network self is missing the fundamental person—its connection to God.

Augustine and Luther after him were simply reflecting on the curse of this inward turn that is our attempt at self-control—that is, the turn away from God and towards ourselves. We are slaves to sin, as Paul wrote (Rom 7:21-25), and that sin is the desire to separate ourselves from God and from others. We call that “control”. The Romantic culture of self-actualisation, fuelled as it is by the power of choice so prominent in free market capitalisation simply aids and abets this journey. The German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who also crossed conceptual swords with existentialism, concluded that self-actualisation is basically the “I” trying to understand itself from itself in a closed system.26

3. The gift of self and the gifted self

a) The gift of a new self in Christ Jesus

i. God send Christ Jesus to offer his-self for mine

The modern self is, to borrow a phrase from Martin Luther, “cor curvum in se”—“a heart turned in on itself”. The self cannot get out of itself to reach the truth. Instead, it must be met by Christ and placed into the truth. Not only is the self separated from God and the world, it actually has no way of reversing itself alone.

Bonhoeffer wrote that what we see in the gospel is that

[Christ Jesus] on the boundary of my existence, beyond my existence, yet for me. That brings out clearly that I am separated from my “I”, which I should be, by a boundary which I am unable to cross. The boundary lies between me and me, the old and the new “I”. It is in the encounter with this boundary that I shall be judged. At this place, I cannot stand alone. At this place stands Christ, between me and me, the old and the new existence. Thus Christ is at one and the same time, my boundary and my rediscovered centre.27

What he’s saying here is that in the gospel, we see Jesus Christ in that space between the self that I cannot overcome and the self that I aspire to be for myself. Christ dies the death that my idolatrous self deserves and brings forgiveness to the self that I cannot justify.

Furthermore, as we read in the New Testament, in the Spirit of Christ, we receive a new identity as children of God. The Spirit of adoption makes the self a gift of Christ, or makes the self-gift of Christ, for the church into a gift of self within the church, so that the gifted self can live a Christ-like life for others. That is, in the power of the Spirit, we say “Yes” to Christ for us so that we can say “No” to the self that is against us.

ii. Through Christ, and in the Spirit, I am given a new self before God

As Paul explains to the church in Romans 8, the Spirit of adoption makes the self-gift of Christ for the church a free gift for the self as he is placed into the church to be a gift for others (Rom 8:15). Through Christ and in the Spirit, I am given a new self before God.

iii. In the Spirit of Christ, I become a gift to the body—the church

Having freed me to live towards God as Father through his Son, God places me in the church among my spiritual brothers and sisters. In this spiritual network that the New Testament calls the body of Christ, I know myself as a gift to them, even as they are God’s gift to me (1 Cor 12:4-11). For the love of God poured into our hearts by the Spirit so strengthens us inwardly that we can submit to one another out of reverence for Christ, who gave himself for us (Rom 5:5; Eph 5:18-21). In the power of the Spirit, we are now free for one another, so that we can, together, enable each other to be the person that God our Father intends us to be.

4. Conclusion

Let me draw things to a conclusion with three questions about self-control in the context of a gospel that I’ve all too briefly outlined.

a) What do we know about self-control in an era of self-actualisation?

What we know about self-control in an era of self-actualisation is that the difference between them is, at a basic level, the goal of such an action. As Paul told the Corinthians, “Everyone who competes in the games goes into strict training. They do it to get a crown that will not last, but we do it to get a crown that will last forever.” (1 Cor 9:25 NIV). The imperishable crown is sanctification for God by his Spirit, having been justified from sin through the Lord Jesus Christ (1 Cor 6:11).

Self-control is a fruit of the Spirit’s directing us through Christ to God as our Father and therefore towards others. Since the Spirit of God lives in us, Christ is at work in us (Rom 8:9-11). Even though our body is dead because of sin, the Spirit gives life because of Christ’s righteousness.

So as Paul says, let us “let us keep in step with the Spirit. Let us not become conceited, provoking and envying each other” (Gal 5:25-26 NIV). Instead, our self-control is the means by which we make the spiritual reality a visible experience for others, as well as ourselves.

b) What should we do about self-control in an era of self-actualisation?

What should we do about self-control in an era of self-actualisation? We should expect the Spirit of God to enable us to be self-controlled. As Paul writes again to the Galatians, “the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control” (Gal 5:22-23 NIV).

We should practice self-control after the example of the Lord Jesus. Or as Paul writes,

Therefore, my dear friends, as you have always obeyed—not only in my presence, but now much more in my absence—continue to work out your salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God who works in you to will and to act in order to fulfill his good purpose. (Phil 2:12-13 NIV)

c) For what can we hope about self-control in an era of self-actualisation?

For what can we hope about self-control in an era of self-actualisation? Our heavenly Father promises that the Lord Jesus intercedes for us when we fail to exercise self-control. Or as the writer to the Hebrews put it, “Therefore he is able to save completely those who come to God through him, because he always lives to intercede for them” (Heb 7:25 NIV). The success of Jesus is always mine, even when I fail.

At the resurrection, we will be given new bodies freed from sin, death and evil—free from the inward compulsions and the outward constraints against self-control. Or as Paul writes, “[W]e ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for our adoption to sonship, the redemption of our bodies” (Rom 8:23 NIV).

[Music]

Advertisements

PO: We’re going to take a break from our program so that I can tell you about our next in-person event. It’s also happening online if you can’t make it in person to Moore College. On the 18th of October starting at 7:30pm, Mark Thompson, Principal of Moore College, will be talking about perseverance. This whole year, we’ve been thinking about Christian virtues. The virtue Mark will help us to think about is the virtue of perseverance.

Christians can often be caught off-guard by how difficult life can be. There are all sorts of things that can hurt us—grief, relationship problems, and hostility from friends and colleagues because we’re Christians. It’s tempting to give up as a Christian or doubt God’s goodness. Yet the Bible encourages us to keep going in the midst of hardship.

The Bible also reminds us that suffering is not a sign of God’s absence or his displeasure, but of his good presence. The Bible affirms that the storms of life we weather serve to refine our faith as we hope in his promises. Mark will help us to think through the idea of perseverance—what it means to keep going as a Christian—and what resources the Bible gives us to keep going as a Christian.

It would be great to see you at the event. If you can’t make it, as I say, it will also be online. The details are all on the CCL website. We look forward to engaging with you in person or online.

Now let’s get back to our program.

Part 2: Discussing practicalities

PO: Thank you, David! I’m going to invite Jordan and Abby to come up. They’re going to chat through some of the practicalities.

Jordan Cunningham: Hi, everyone! It’s so good to be with you. Again, I’m Jordan and this is Abby. We are two of the model students here at college. I couldn’t help but notice you left that out, Peter! [Laughter] But anyway, it’s our pleasure to be with you this evening. What we’re going to do just for the next few minutes is really to attempt to grab hold of a couple of the really helpful things that David has shared with us, and we’re going to open the conversation about what it means to bring some of these things to bear practically. We hope that this conversation will, perhaps, kickstart some of your own thinking, and also continue to fuel the questions, which David will then field afterwards.

Without further ado, Abby, where are we going to begin?

The personal benefits of self-control

Abby VanMidde: We’ve heard tonight that self-control is something that we should desire, compared to self-actualisation. I guess the question that comes to mind is, “Is there actual benefits to self-control?” What benefits have you experienced? Is it something we should do—an obligation? Or are there actually joys and great things about self-control?

JC: Yeah, absolutely. I think for me, one of the most helpful ways to approach this is really from the Apostle Paul’s rhetorical question in Romans 6: he says, “When you were slaves to sin, you were free from the control of righteousness” (Rom 6:20 NIV). You could also say, “Whenever you were slaves to sin, you were free from obligation to self-control”. But then he asks them, “What benefit did you reap at that time from the things you are now ashamed of?” (Rom 6:20-21 NIV). He says, “Christian: when you look back before your Christian life, or perhaps even at a more immature stage of your Christian life, when you were more into the process of self-actualisation—of doing what you wanted when you wanted, fulfilling your desires, looking only inwardly—do you look back on those times and think, ‘Gosh, life was just so much better’? Do you look back on those times and say, ‘My relationships were founded on so much better things. My joy was deeper. My life just reflected such a better order, and everything, by and large, is now so much worse, now that I have given myself to follow Jesus and exercise self-control’?” I think in the Christian experience, the answer is a profound “No!”

I think part of the reason for that is there is an amazing proverb and it puts self-control in these terms: “A man without self-control is like a city broken into and left without walls” (Prov 25:28 ESV). There are many ways you could unpack that image, but one of the things it tells us is that the person without self-control lacks those walls—those protective barriers—to avoid letting a lot of the bad things in, but also to stop the good things being taken out. I think that is profoundly helpful for us in the Christian life: self-control is one of the godly means of grace, which Jesus builds in us through his Spirit, so that we can avoid slipping into a lot of bad habits, and also avoid having the goodness of his truth robbed from us. We’ll explore that a little bit more in just a moment.

For now, Abby, that’s just some of the ways that I’ve personally experienced benefits.

The communal benefits of self-control

JC: But how do you think personal self-control can benefit communal life? What did your personal self-control do for our church communities, our families or our friendship groups that self-actualisation cannot?

AV: Yeah. I thought the comparison of self-actualisation and self-control was quite stark, and the effects that they have on the people around us. As David pointed out, self-actualisation is really about having our goal as the authentic self. We determine ourselves by our own emotions, desires and dreams. That’s what we’re using to motivate us towards this self.

You can see from some of the impacts of the effects of that on society that David pointed out—like the youthful suicidal madness of the Romantics, or the narcissistic irrational mass movements like fascism. It’s pretty clear: those aren’t good things! Self-actualisation does not do good things for society—for our friends, our families, our churches.

But in contrast, as David talked about, self-control coming about as we’ve been given a new self in Christ gives us a different goal—an eternal goal—and that goal benefits the body together. So as we exercise self-control, we actually become a gift to the body of Christ. There’s huge benefits for people around us.

As I think about a practical example of this, one might be how we use our money. If I’m trying to realise my authentic self, I might use my money to buy an identity—a certain identity that I want to have. Whether it be through buying certain clothes or a car, I can promote myself in a certain way for my own gain. But as a new self in Christ, if I’m exercising self-control, I can actually invest in things of eternal value that are going to benefit the church and the body of Christ. I can exercise self-control in not spending money on myself, but giving it to church or to missionaries or to those around me who are in much more need. That obviously benefits them over just doing what’s best for myself.

That’s just one example. I’m sure there’s many more where exercising self-control is so much more beneficial for those around us.

Self-control in practice

AV: In light of that, we’ve touched on a little bit of what self-control can do for us personally and for one another. But what does it actually look like? What do we mean when we’re talking about self-control? What’s the practice of it?

JC: Yeah, well, I think I’m going to go for the really obvious options. I’m going for the application that you’re probably sick of hearing almost every single Sunday. The first thing I’m going to point to are those practices of common grace that God has given us—of coming to learn from him in his word, coming before him in prayer, and gathering with his people regularly.

I read a book recently. It was about marketing and research branding. What it communicated was that now, in the 21 st century, we aren’t just seeing hundreds of advertisements a day; we’re actually seeing thousands, whether it’s walking down the street, seeing them on TV or just looking at your smartphone. Even though all of those things won’t necessarily be bad, what they all culminate in for us in many different ways is this message of self-actualisation that David has just walked us through—that we as Christians are continually being bombarded with messages about how to keep ourselves number #1 and how to find self-fulfilment in doing what I want when I want.

Thinking about that in the Christian life: for example, if you ate nothing but junk food Monday to Saturday every single week, but then every Sunday, just for one meal, you decide to eat something that’s good for you, and then you repeat that process week after week after week, in what state do you think your health would be after about a month? You see where this is going. In a very similar way, if as Christians we are constantly being trained and catechised by the culture to self-actualise and our intake of godly self-control and discipline through the means God has given us is relegated to a couple of very short moments throughout the week, our spiritual health is probably going to suffer. We’re going to find it very very hard to exercise self-control.

So I want to do what every preacher does almost every single week and hold up again those great practices of opening the word, coming before God in prayer, and meeting with his people so that it is far easier to keep Jesus as number #1 in our lives—to actually have that perspective to remember the one for whom this is all worth it and the one in whom we trust—that his self-control that he gives us through the Spirit gives far more fullness of life than anything the culture can offer in the form of self-actualisation.

What about you, Abby?

AV: Yeah, there’s many ways, obviously, in which this plays out. I think one of them that I was mulling over and thinking about as I think about self-control and its practicalities is how I exercise self-control in relationships—particularly in my marriage. I think sometimes I have the tendency to think, “Oh, it’s 50/50: I give in what I get out”. I wonder if it’s marked with a bit of that self-actualisation—that actually my marriage is there to benefit me, to build me up; I should be getting something out of it. So when I’m not, I don’t actually feel like putting much into it.

But I think it’s helped to realise our new self is in Christ and we are able to deny ourselves and realise that, no, it’s not 50/50; I put in 100 per cent, no matter what I get out, because it’s about controlling myself—controlling my desires—and investing in something not for the sake of getting something out of it, but because there’s a greater goal.

In Ephesians 5, it’s pretty clear that marriage isn’t a selfish thing; it’s actually a selfless thing. It’s death to the self as the centre of marriage, not self-gratification. It’s even obvious in Jesus’ own self-sacrifice: he denied himself, he took up his cross, and he calls us to do the same. So I wonder if self-control helps in those sorts of relationships as well—whether it’s marriage, other familial relationships or friendships that we see play out benefitting us, benefitting the other.

For other examples of self-control, I think our minds go to things like exercise, food, technology (which is a huge one), entertainment and alcohol. Exercising self-control in these areas is recognising those desires in us are actually sinful and wrong, and so restraining them and instead choosing to use our whole selves—controlling ourselves for God’s glory.

I think there’s a lot of complexities around that that I won’t go into.

JC: Yeah, well, as you all know yourself, there’s many many more places we could go. But of course, what could be better than to help you continue down the pathway of self-control than by committing to come back to all our future CCL events [Laughter] and tune into the podcast on a regular basis. Thank you.

[Applause]

Conclusion

PO: Thank you very much, Jordan and Abby. Jordan mentioned the podcast: please do subscribe to the podcast. Each month, we try to release two episodes that address different areas of the Christian life.

Then finally, we’d be very grateful if you would prayerfully consider partnering with CCL financially. At the beginning of this year, we moved to run CCL exclusively on donations, which means we don’t charge for our events. Our hope is that moving in that direction will help more people to access our resources and invite more partnership. So if you’re interested, you can find detail on the website and more information there. That would be wonderful.

I will pray and we’ll finish the formal part of our meeting.

Our Father,

We thank you for the Lord Jesus. Lord, we thank you for your Holy Spirit, and we thank you for the fruit that he produces in our lives. We pray that each of us would be marked more by lives of self-control and that that would spill over in how we love you and how we love our neighbour as ourselves.

Father, we pray that you might be glorified in this, and that our lives might increasingly be a pleasing aroma that brings honour to the Lord Jesus.

We ask this in Jesus’ name. Amen.

[Music]

CK: To benefit from more resources from the Centre for Christian Living, please visit ccl.moore.edu.au, where you’ll find a host of resources, including past podcast episodes, videos from our live events and articles published through the Centre. We’d love for you to subscribe to our podcast and for you to leave us a review so more people can discover our resources.

On our website, we also have an opportunity for you to make a tax deductible donation to support the ongoing work of the Centre.

We always benefit from receiving questions and feedback from our listeners, so if you’d like to get in touch, you can email us at [email protected].

As always, I would like to thank Moore College for its support of the Centre for Christian Living, and to thank to my assistant, Karen Beilharz, for her work in editing and transcribing the episodes. The music for our podcast was generously provided by James West.

[Music]

Where noted, Bible quotations are also from THE HOLY BIBLE: NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by International Bible Society, www.ibs.org. All rights reserved worldwide.

Where noted, Scripture quotations are from The ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Endnotes

1 Editor’s note: This quote has been wrongly attributed to Aristotle (see Sententiae Antiquae, “‘Braver by Overcoming:’ Some More Fake Aristotle”, 20 March 2019: https://sententiaeantiquae.com/2019/03/20/braver-by-overcoming-some-more-fake-aristotle/), but David’s point is still stands.

2 Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility (London: Thomas Egerton, 1811), chapter 48.

3 Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity (Cambridge: CUP, 1989). See also Kathleen Wallace, “You Are a Network”, Aeon (2021): https://aeon.co/essays/the-self-is-not-singular-but-a-fluid-network-of-identities.

4 Kathleen Wallace, “You Are a Network”.

5 Nikolas Kompridis, Philosophical Romanticism (London: Routledge, 2006).

6 Tim Blanning, The Romantic Revolution, Modern Library Chronicles (New York: Modern Library, 2012) 24.

7 Blanning, The Romantic Revolution, 26.

8 Robert J Richards, The Romantic Conception of Life (Chicago: Unversity of Chicago Press, 2002).

9 Peter Watson, The German Genius (London: Simon & Schuster, 2010).

10 Reading, writing and arithmetic.

11 Blanning, The Romantic Revolution, 57ff.

12 Fredrick C Beiser, The Romantic Imperative (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2003) 103.

13 Beiser, The Romantic Imperative, 103.

14 Editor’s note: David said “Herder” in the recording, but it’s actually Beiser who wrote this.

15 Beiser, The Romantic Imperative, 104.

16 David Kolb, “Authenticity with Teeth”, in Philosophical Romanticism, ed Nikolas Kompridis (London: Routledge, 2006).

17 Blanning, The Romantic Revolution, 87.

18 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (London: W Strahan and T Cadell, 1776) I.ii.3.

19 Quoted in César García, “Searching for Benedict Spinoza in the History of Communication: His Influence on Walter Lippman and Edward Bernays”, Public Relations Review, 41, no. 3 (2015), 321: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0363811115000053.

20 Edward L Bernays, Propaganda (New York: Horace Liveright, 1928), chapter 4.

21 Edward L Bernays, Public Relations (Boston: Bellman, 1945), chapter 14.

22 Clive Hamilton and Richard Denniss, Affluenza (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2005) 13.

23 Ibid.

24 Dan Cryan, Sharron Shatil, and Piero, Introducing Capitalism (London: Icon, 2013), 129.

25 Alexander Stern, “Authenticity is a Sham”, Aeon (2021): https://aeon.co/essays/a-history-of-authenticity-from-jesus-to-self-help-and-beyond.

26 Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Act and Being, trans Martin Rumscheidt, Engish edition, vol 2, DBWE, ed Wayne Whitson Floyd (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1996).

27 Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Christ the Center, trans Edwin H Roberston (San Francisco: Harper, 1978) 60.